Author: Gershon Ben Keren

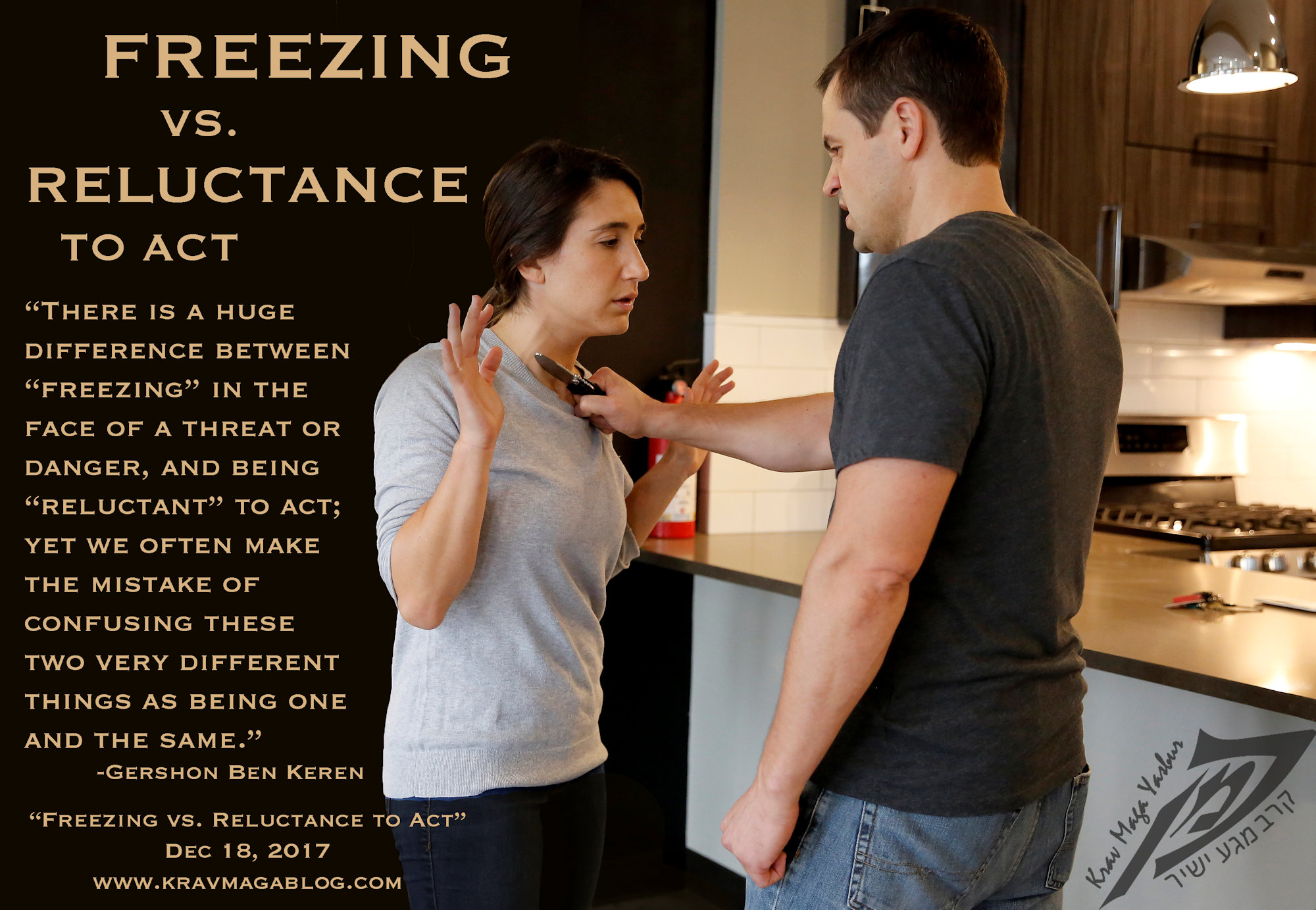

There is a huge difference between “freezing” in the face of a threat or danger, and being “reluctant” to act; yet we often make the mistake of confusing these two very different things as being one and the same. When somebody truly freezes, they are experiencing an emotional response to danger, however once this passes (and this often happens before they are physically attacked – as most assaults happen face-to-face and are preceded by dialogue), an individual is still left with their cognitive process intact, and so has the ability to act. Unfortunately, many people will still fail to do anything, even when their abilities to physically respond to a threat return, and it is often this reluctance to engage that creates the inaction that leads to a person failing to deal with the danger they face. Even a seemingly trained and prepared individual, may fail to respond because of a reluctance to act, rather than because of freezing, and in this article I want to examine some of the reasons, why people don’t respond to an assault/attack, in a way that their training suggests that they would.

In many ways, the better your training, and the greater your preparation, the more pressure you have on yourself to perform well. A black belt in any martial art, has an expectation on them, to be able to easily deal with any untrained individual i.e. they supposedly possess the knowledge, the skills, the fitness and the techniques, that make them a superior adversary to the aggressor(s) who they are facing etc. However, most people training in martial arts and self-defense (and I include myself in this), have a dirty little secret; that they fear real-life violence (as they should), and understand that it is their training alone, which gives them the edge against an experienced and committed aggressor. I never ask anyone to be honest with me concerning this, I only ask that they be honest with themselves. The issue is that a person’s training is an “external” thing; it is something that they have applied to their lives – it is not something that is intrinsic to who they are, and this means it is something that they must have faith in, and develop a trust in themselves to apply – the goal of the martial arts being that over time this starts to transform who they are, however it is far from an overnight process. If this is lacking in any way, shape or form, an individual will be reluctant to put their trust in it. It doesn’t matter how authentic, proven or “battle-tested” it is, when it comes time for a person to enact a solution for themselves, it is down to them to make it work. I still remember the first punch I threw, as a professional, and 99.9% of the power came from a hope and a prayer that it would do what I knew it was capable of doing in the training environment. I had to drown out every doubt I had, with the belief that it would accomplish the goal of significantly stunning, and slowing down, the person I was facing. It was a pre-emptive strike, and I was reluctant to throw it, because I wasn’t sure that I could trust it to work. As an instructor, I spend a lot of time, developing student’s convictions in their skills and abilities to be successful, whilst at the same time giving them realistic expectations as to their assailant’s responses.

Many people are reluctant to act, because they believe a better opportunity may come along; that “now” is not the right time. I believe that what separates the effective martial artist/self-defense practitioner from the ineffective one, are not superior skills and techniques, but decisiveness. It doesn’t matter how good you are, how effective your techniques are, etc., if you are not decisive and are too reluctant to act, your aggressor/assailant will never see these. Successful fighters, in real-world situations, are not often the most skilled and able, but the individuals who are committed to acting first. If you are continually waiting for a better opportunity, the other person is likely to overtake you. When I first competed as a Judoka, I was always reluctant to attack, telling/convincing myself that there would always be a better opportunity, that now was not the right time, etc. Most of my initial fights were lost on penalties for being too defensive and not aggressive enough. After a while I realized that nobody would give me that perfect opportunity, and/or that if it was presented I’d usually miss it. The perfect moment, is the one you create, not the one you wait for, and often you create it by moving events forward, rather than by waiting for things to align. If you need to take a knife away from your throat, because you believe somebody is going to cut you, you’ve got to do it – and often force yourself to do it – rather than wait to see if the perfect, or a better moment come along; they won’t.

Unfortunately, reluctance is built into our DNA – if something is not causing us pain now, we are hard-wired that it is better to do nothing than risk changing that, even if/when we know we are likely to experience pain in the future. If somebody is pressing a knife into your neck, and demanding that you move with them, you know that you shouldn’t i.e. they obviously need to move you somewhere else, because they can’t do to you what they want in their current location (which means dealing with the threat/danger there is probably your best survival chance/opportunity). However, in that moment, you are not experiencing pain. You are aware of the future possibility of pain, but in that moment, you are not being hurt. Your survival instinct will tell you to do nothing to change that. Action means the risk of that changing, inaction means preserving the status quo, and so you will be reluctant to act. Many times, this will be excused, or explained away, as freezing, but it is not: it’s a reluctance to act and deal with the danger. As those practicing and preparing for reality, we need to be aware of the difference, and train not just to overcome a potential “freeze” response but also a “reluctance” to act.

Social media, has provided many examples of this reluctance. Most of us will have seen footage of law-enforcement officers not drawing their weapons, even when the situation was obviously one where they were entitled to do so. In some cases, these individuals emotionally froze, but in most they were too reluctant to escalate their level of force, and these are trained individuals (the reason I am using them as an example). Some, may be reluctant because they know the potential legal consequences of drawing their weapons, some may be reluctant to act in this way due to moral concerns etc. There are a whole host of reasons, however in many cases it is a reluctance to act that holds them back, rather than their “freeze” response. These are trained individuals, who deal with violence on a near daily basis, and yet they can fall foul of this indecisiveness, and we should be aware that we can too. Rather than blaming inaction solely on freezing, we should consider the reasons why we may be reluctant to act, and train to overcome them. We’ll take a look at some of the ways we can do this, in the next blog article.