Author: Gershon Ben Keren

One of the first pieces of advice I remember receiving when I started working bar and club security was that you only think about the first punch/strike you throw – after that, you’re not really thinking, you’re just doing i.e. the only decision you make in a fight, is to fight. I don’t fully agree with this, but it comes close to recognizing that most of what you do in a fight isn’t about conscious processing or reasoning; there isn’t the time to engage in such thinking patterns, as everything will be moving far too fast. My elevator pitch, self-defense lesson, is get a hand in your assailant’s face (conscious choice/decision) and start striking (unconscious process) until you recognize a disengagement opportunity (unconscious/conscious choice/decision). It’s not a particularly sophisticated strategy, but it’s a good starting plan. Unfortunately, our conscious processing often gets in the way of our ability to fight effectively, because it causes us to be hesitant and indecisive – two behaviors that usually result in disaster. In this article, I want to look at how our attitude and thinking in the training environment can either help or hinder us, and how we can simplify our thought processes so that they don’t get in the way of our ability to be effective when engaged in a conflict.

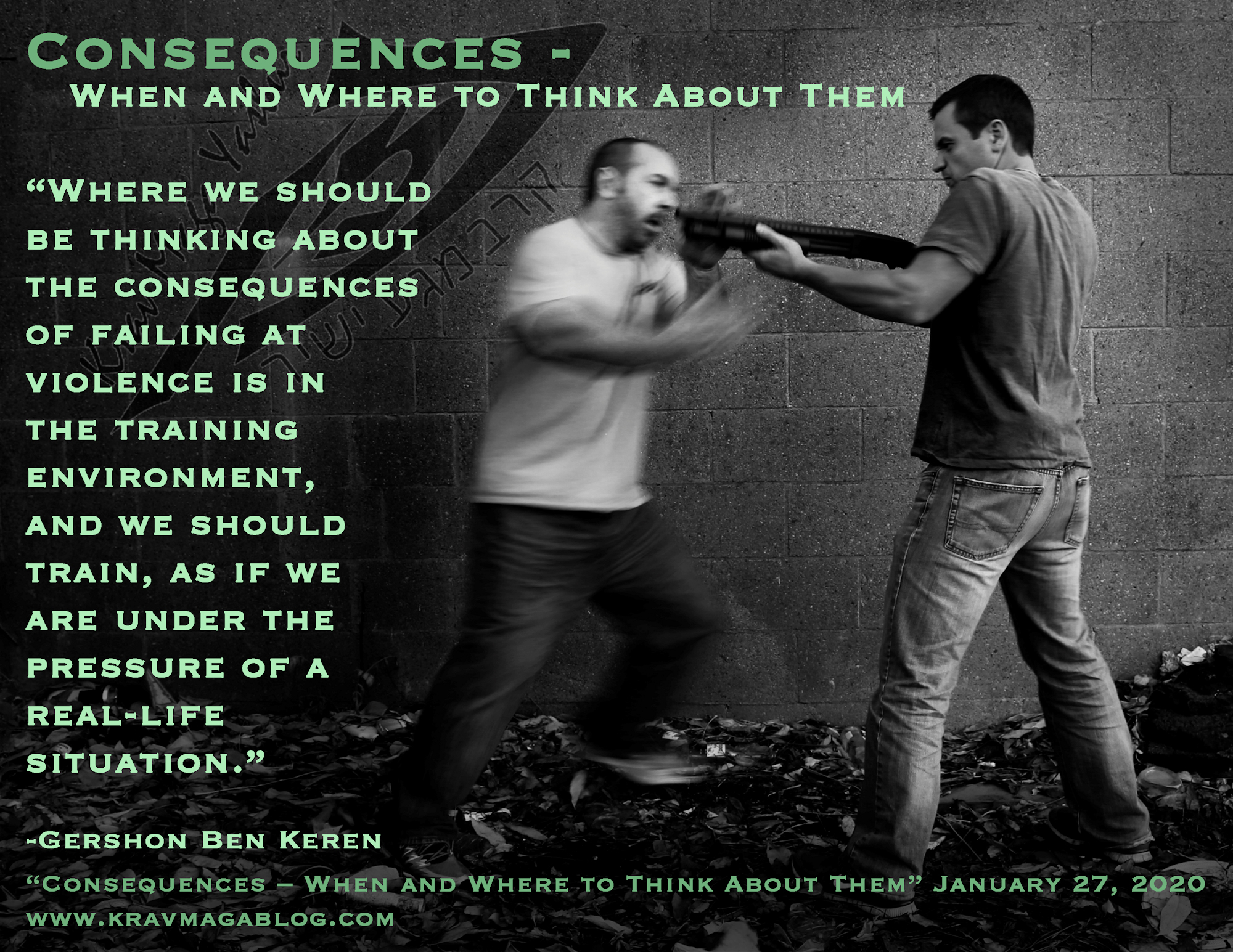

When gun disarming, if you don’t get out of the line of fire – whether that’s accomplished by you moving, you moving the weapon and/or a combination of the two – and your attacker pulls the trigger, you’re getting shot. Broken down in this way, it’s a pretty simple scenario, with an obvious consequence, however if you’re training with a Blue Gun or a non-firing replica, the consequence isn’t felt i.e. you don’t get out of the line of fire, you don’t get shot, etc. There are easy ways to create a “safe” but “felt” consequence such as using simunition, paintball or airsoft weapons, etc., to check that students are indeed getting out of the line of fire, but once they return to training with non-firing replicas, this consequence is once again lost; and it becomes easy to forget the purpose of training – that is the training “goals” can become muddled and confused. In a weapon disarm, the goal is to end up with the weapon in your hand(s) and not in your assailant’s and/or training partner’s. However, there is a lot that can and does happen between the start of the process and the end; including the assailant’s response and reaction, whether trained or natural e.g. their grab/snatch reflex is triggered and they automatically pull the weapon away as they feel it being controlled, etc. If your goal when training is simply to get the (non-firing) training gun, out of your partner’s hands as quickly as possible, then this can be accomplished without getting out of the line of fire – when this happens, any body defense that should be present either becomes ignored or neglected; all the work is done with the hands. The goal has been changed from learning a technique and solution that would be effective in a real-world scenario, to one of “how can I take this plastic weapon off my partner as quickly as possible in this training environment”. Every time we train a technique – whatever it is – we must remind ourselves of the consequences if this was a real-life situation. In a real-life situation, we must do the opposite, and forget about the consequences.

In a real-life scenario, if we get caught up thinking about the consequences of our actions, we will find ourselves freezing, hesitating and being indecisive. If you were to have somebody point a gun at your head – and you understood that if you didn’t attempt to disarm them they would shoot you - it would be natural to think about all the things that could go wrong i.e. in this moment your life is in question and there are obvious consequences for you, your family, and your loved ones if you were unsuccessful in getting out of the line of fire. However, none of these consequences are relevant to the execution of the technique/solution. The mechanics of the disarm are exactly the same as that which you have practiced with a plastic weapon in a training environment, if, and it’s a big “if”, you have practiced them in that environment with the consequences in mind e.g. taking into account what can happen if you don’t get out of the line of fire. It is the considering, and taking into account, the consequences in the training environment, which makes the training effective. If we do this, we know we have something that is able to work in the real world, allowing us to execute a solution in a real-life scenario as if we were doing so in a training environment, etc. Obviously, this is a gross simplification of what violence actually looks like, however I’ve done this in an attempt to demonstrate when and where we should be thinking of the “consequences” of what we are doing.

Not thinking about the potential consequences of our actions in a real-life setting isn’t an easy thing to do. I’m reminded of this in Soccer/Football every time a world cup game goes to a penalty shoot-out. A player may have practiced taking penalties over and over again, with an almost 100% success rate, however if their goal is needed to keep their team/country in the championship, although the task remains the same as what they practiced so successfully in training, there is the danger of buckling under the pressure of the consequences of failing. If they can remove that pressure and make the task simply about putting the ball in the back of the net, and nothing more than that, then their chances of success will rise dramatically. Where we should be thinking about the consequences of failing at violence is in the training environment, and we should train, as if we are under the pressure of a real-life situation e.g. when gun-disarming, getting out of the line of fire isn’t optional, so that if/when we are confronted with a similar real-life situation, all we have to do, is replicate what we did in training.