Author: Gershon Ben Keren

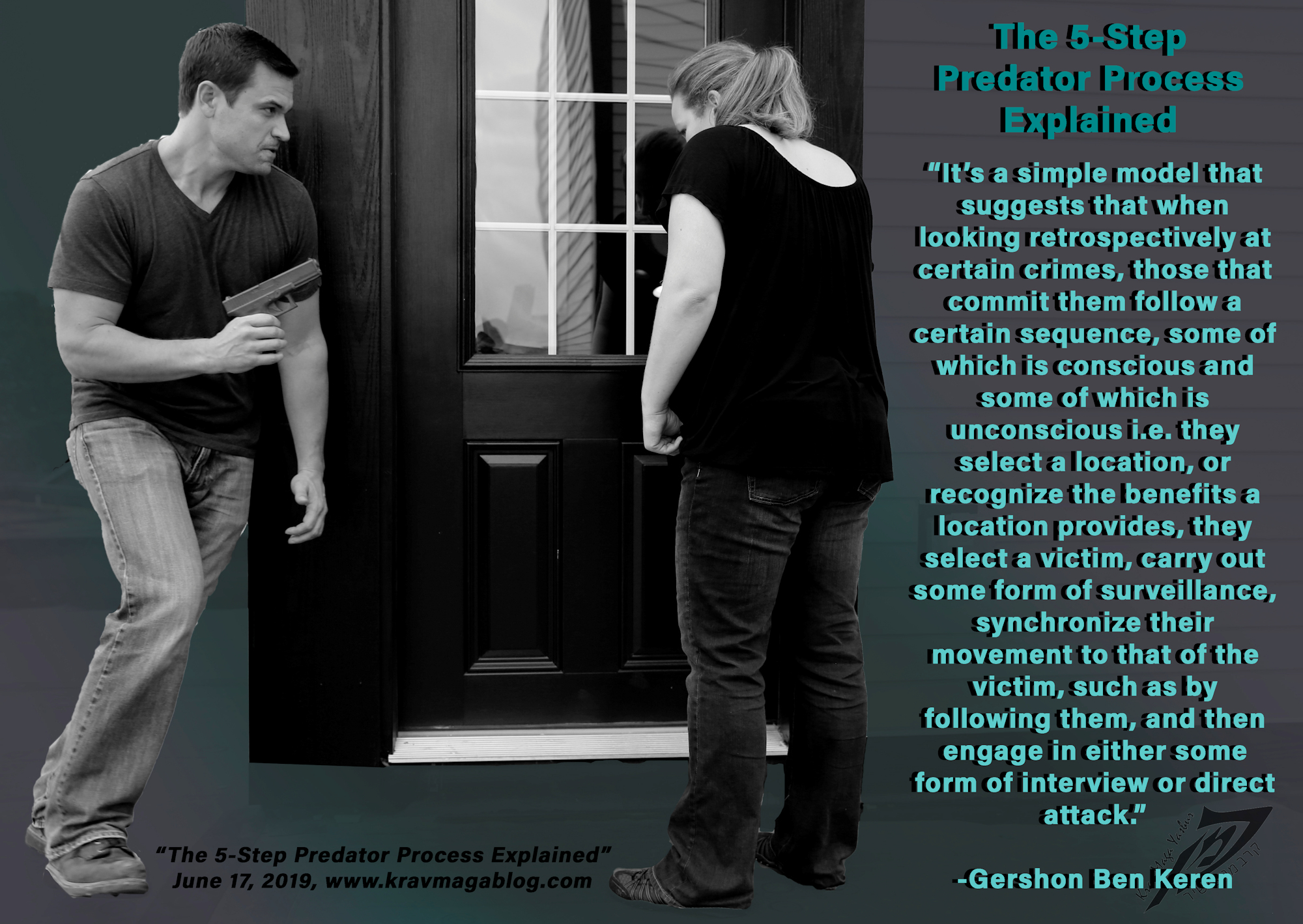

About 15 years ago, I developed a framework for my corporate clients, expressing how certain premeditated acts of violence and crime are committed; I termed it the 5-step predator process (the title being influenced by similar work that was being undertaken by criminologists at the time around the stages of grooming that pedophiles take their targeted victims through) – I wrote briefly about it in this blog around 6 years ago. It’s a simple model that suggests that when looking retrospectively at certain crimes, those that commit them follow a certain sequence, some of which is conscious and some of which is unconscious i.e. they select a location, or recognize the benefits a location provides, they select a victim, carry out some form of surveillance, synchronize their movement to that of the victim, such as by following them, and then engage in either some form of interview or direct attack. In this article, I want to look at some of the ideas underpinning this model/framework, as well as some of its limitations i.e. what it is not able to explain and demonstrate, etc.

The first thing to note about the model is that it is situational. Often when a theory or idea is proposed it is taken to be a “general” theory that attempts to explain everything e.g. Felson and Cohen’s (1979) Routine Activity Theory is often presented as a general theory, because it attempted to explain and show how overall crime rates changed in the United States between 1947 and 1979, however what they were really measuring were certain types of crime, that accounted for these changes. Their proposal that for a crime to be committed there must be; a motivated offender, a suitable target, and the absence of a capable guardian, has merit in explaining certain types of street crimes, but as Feminist Victimologists have pointed out, needs a certain degree of adaptation to explain domestic violence, and familial child-abuse, where in simplistic terms the “capable guardian” - who is seen to deter and prevent certain types of crime - is the motivated offender in others. Likewise, the 5-step predator process model attempts only – in a very loose way – to explain criminal processes wherein the perpetrator and the victim have no formal or identifiable relationship. If a criminal has already identified a target - such as the partner of their friend - for a rape/sexual assault, the selection of location becomes less important to understanding that crime, than the relationship they have with the individual they are planning on victimizing. I often use the abduction and murder of Amy Lord to illustrate this. In 2016, Amy Lord, a mid-twenties South Boston resident was beaten in her flat and abducted, before being taken to a series of ATM’s to withdraw money, and then driven to Hyde Park, before being stabbed to death. On the Saturday afterwards, our free women’s self-defense program was packed with women in their mid-twenties from South Boston who feared that a killer was targeting women in their specific location - a it turned out, they were correct. However, if Amy Lord’s killer had been a past boyfriend, that relationship would have been the driving factor in her murder, and the fact that she lived in South Boston far less relevant. Crime and Violence is situational, and two of the five situational factors that can pivot how a violent act is understood, are “Location” and “Relationship”. The 5-step process I use, is only applicable where there is no existing relationship between the perpetrator and the victim i.e., the victim is chosen/targeted in a location.

Another foundation of the model is a mathematical one, that underpins a lot of behavioral sequences in psychology, and comes from the mathematician Andrey Markov; the Markov Chain. Basically, Markov Chains look at sequences, going in one direction: forward, i.e., the current step or stage - and not any of the previous ones - is only relevant to the next one; the cumulative history is not relevant to the next step in the sequence. In the 5-step model, this would translate in the following way: after victim selection, comes the surveillance phase, however the selection of a location isn’t relevant to this step in the chain, as it occurs. This doesn’t mean that certain locations aren’t chosen for the concealment and surveillance opportunities they may provide, but that this is part of the process in choosing a suitable location i.e., the first step in the chain, and this choice isn’t as relevant to the act of surveillance, as to the selection of a potential victim. When looking at such models in a Markovian Chain, this is referred to as lag-one i.e. it is only the last link in the chain that is relevant to the next. This becomes a very important idea and concept when looking at impulsive and opportunistic behavioral sequences, where what is happening in the moment dictates what happens next – a common feature in violent crimes, even when there has been a fair degree of planning. It also reduces a lot of complex rigidity and allows the model to represent fluid and dynamic situations.

Another idea of the model is that certain phases of the sequence can run concurrently e.g. surveillance can occur at the same time as a synchronization of movement e.g. a perpetrator can select a victim, and as they follow them, synchronizing their movement, as they carry out their surveillance, etc. Because the process is modeled as a Markovian Chain, it is the synchronization of movement that is affected by the surveillance phase, that occurs after the victim selection step; and you obviously can’t carry out surveillance on a victim, until you’ve selected them, or been in a location where they exist. A perpetrator’s surveillance may be as simple as watching a selected victim to confirm that they were correct in choosing them, and they may combine their synchronization of movement to help influence this. Several years ago, there was a serial rapist operating in the North End of Boston, which is a rabbit warren of narrow, winding streets. One of the women who was victimized reported that she had picked up that she was being followed, and decided to stop and pretend she was on her phone, so that the person behind would a) know that someone knew where she was, and b) respect the social convention that you don’t interrupt somebody’s phone conversation. It may be that the attacker used his movement to gauge his target’s response, as part of the surveillance phase, to judge whether they were likely to fight back or not e.g. would they turn around and verbally confront him or ignore him, hoping that he would pass them by?

There have been attempts to present general theories of crime, but often these become so general that they offer little in way of explanation, and it is often more useful to use several theories and models to explain acts of violence and other crimes. The 5-step predator process model/framework is something I use to give a sense of how violent crimes, committed by strangers, occur, however there will always be certain situations that don’t fit neatly into it, often because relationships between perpetrators and victims aren’t so black and white or clear cut e.g. in certain neighborhoods/locations, victims and aggressors will rub shoulders with each other on a daily basis, but not have a strong relationship with each other, clouding how the two situational factors of location and relationship affect each other. However, as a means of explaining how certain criminal behaviors can be predicted and identified, I have found it to be an extremely useful framework.