Author: Gershon Ben Keren

It may be because I’m British that I’m very interested in medieval history. Perhaps because school trips often involved going to various castles – “if you want to know what the weakest part of a castle is, it’s the gift shop”, as Bill Bailey put it. I think to small children, castles are representative of safe spaces i.e., once you are behind the walls, the gates shut, the portcullis down, and the drawbridge lifted, you feel safe etc. If the castle has a moat, you know siege towers and ladders will be ineffective, and nobody will be able to tunnel under the walls etc. My interest in castles and medieval history started around the age of six or seven, a period in childhood development, when more abstract notions of safety start to progress and expand – such as what if a country invaded another country – and so the relevance of castles to safety start to be understood. However as defensive technologies, such as castles developed, so did offensive technologies, such as the trebuchet, which was able to throw large objects such as boulders across a moat to smash a wall etc.

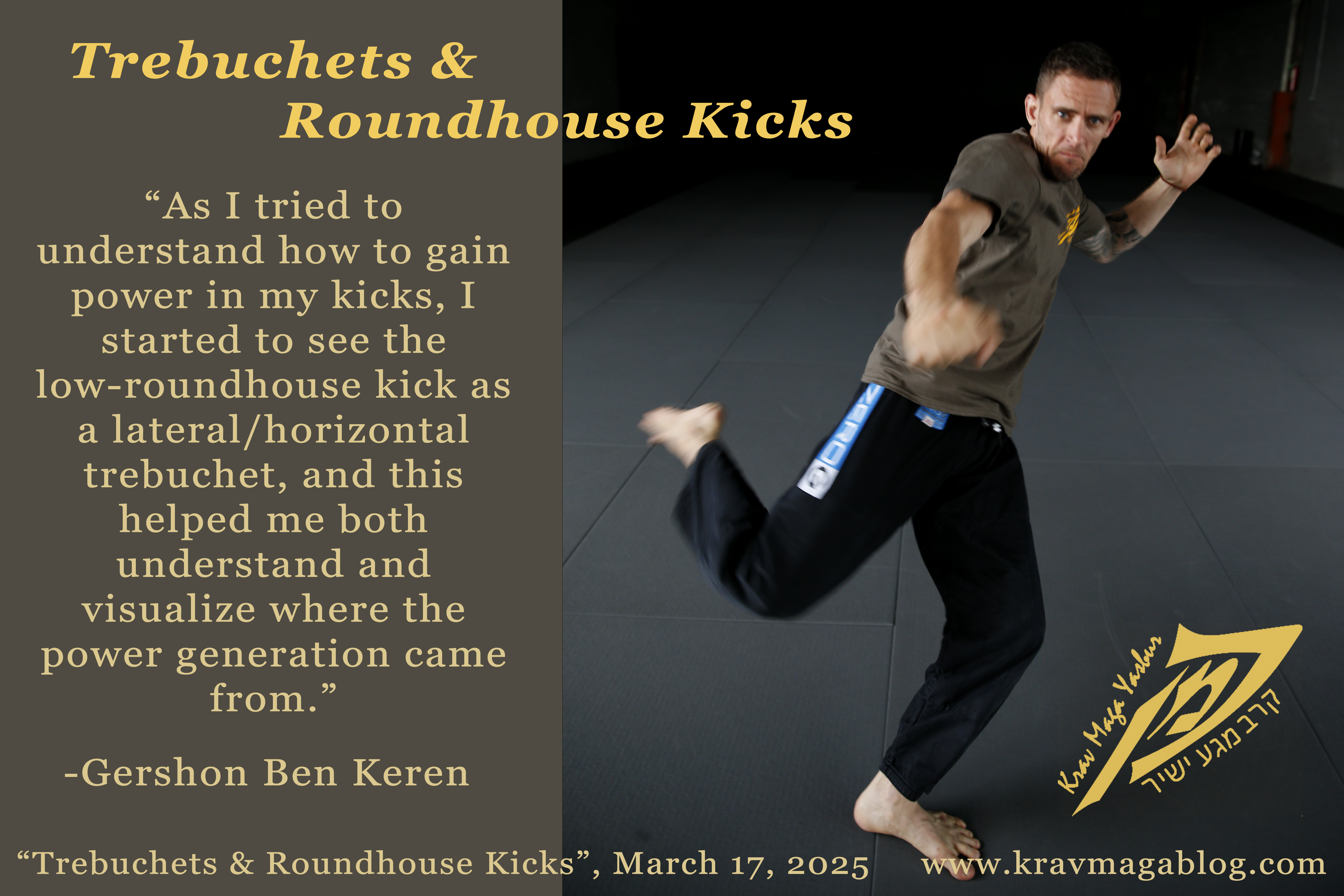

The first martial art I studied was Judo, so my introduction to fighting systems/methods etc., was as a grappler. I started training Karate a few years later, and it was my understanding of trebuchets which helped me improve my roundhouse kick. I still use the example of the trebuchet, when explaining and teaching power development in roundhouse kicks. Whilst I understand and acknowledge that there are many different ways to throw a roundhouse kick, when it comes to developing power, common principles apply, and I’ve found that the trebuchet displays these graphically/vividly.

The first trebuchets were traction powered and referred to as “traction trebuchets” or “traction engines”. Like a lot of later siege engines/weapons they were developed in China. These machines involved people pulling a rope attached to a long beam/lever that launched a sling loaded with a projectile. The limiting factor of such machines was the amount of power that could be generated by people pulling on the rope; they had to be able to be able to both overcome the inertia of the beam and the projectile. By medieval times the counterweight trebuchet had been developed. Unlike the traction trebuchet, which relied upon human power, the counterweight trebuchet used a large, heavy weight (usually a cradle loaded with rocks and stones) attached to the short arm of the beam. When released, this counterweight would fall/drop, causing the longer arm of the beam to swing upwards and hurl the projectile from a sling attached to the end. Isaac Newton said that with a solid object to base it on, and a long enough lever he could lift the world. The power that a lever and a counterweight can exert is quite extraordinary. In 1304, which saw the First War of Scottish Independence, King Edward 1st of England used a giant trebuchet known as “War Wolf” to demolish the walls of Stirling Castle, with projectiles that weighed up to 300 pounds, over distances of 300 meters/1000 feet. The two main components of a trebuchet are: a counterweight, a lever arm (a short part, and a long part, with a pivot point) and a sling. It is by understanding how these things work together that we can understand and reference how the power in a roundhouse kick is generated.

When I first learnt to throw a low roundhouse, I thought/believed that the power came solely from the leg – not realizing that this was part of the delivery mechanism rather than that of power generation. As I tried to understand how to gain power in my kicks, I started to see the low-roundhouse kick as a lateral/horizontal trebuchet, and this helped me both understand and visualize where the power generation came from. I visualized my upper body being the counterweight, my upper leg as the beam, and my shin as the sling. Because I couldn’t “drop” the counterweight, I had to turn it as fast as I could, allowing the upper-leg to be dragged behind it, with the lower leg/shin being allowed to act as a “sling”, with centrifugal force extending it into the target. Once I started to understand that it was the speed of the counterweight/my upper-body turning, and that the leg was pulled round by this – like a lateral/horizontal trebuchet – my kicking power started to improve. I started to think less about the leg aspect of the kick and more about the importance of the counter-weight i.e., turning the body.

When many historians first looked at tapestries and pictures depicting trebuchets on wheels, it was believed that the wheels were used as a means of transportation i.e., to get them from one siege to another etc. However, when it started to be understood that trebuchets such as War Wolf were broken down into parts in order to move them the role of the wheels started to become examined/studied. It was found that the dropping counter-weight, also pulled the trebuchet forward, allowing for more power to be generated, than if it were fixed or mounted into the ground etc. When I learnt this, I started to understand that turning the supporting foot, when making the kick wasn’t something I had to actively do, and instead just let happen i.e., it was the turn of the body/movement of the counterweight, that pulled the leg round, and I just had to be light enough on that foot to allow it to “naturally” turn with the movement; like allowing the trebuchet to “roll” forward when the counterweight dropped.

I am a firm believer in trying to understand something or increase an understanding of something by examining it from a number of different directions and perspectives. Often when I find myself wanting to understand something I try to dig deeper, when it is actually more productive to look at/study something in a different field/area, and have the subconscious mind make a connection for me. Trying “too hard” when practicing my kicking didn’t get me anywhere however when I saw, understood and visualized it from a totally different perspective I made progress.