Author: Gershon Ben Keren

If you are involved in a violent altercation where you must make the claim of self-defense, there is a very good chance that this claim will be tested in court. Claiming self-defense, means that you are admitting that you used violence, but were justified in doing so for your own protection, etc. One of the pieces of evidence in such a case is that of witness statements, and these can be extremely unreliable. For this reason, in England and Wales a criminal case can’t be brought against another person if it relies solely on eyewitness testimony; there has to be other corroborating evidence. The Innocence Project, in the US, that looks to exonerate wrongfully convicted innocents using DNA testing, has found that 71% of those who were found guilty of crimes they didn’t commit, had been convicted due to mistaken eyewitness testimony. Even though a victim and/or witness may appear credible, believable, and confident in their recollection of events, people and places, it doesn’t mean that their memories are accurate and reliable – in fact, it is more likely that an individual will be convinced that a memory is accurate, the more easily they can recall it i.e. the greater the cognitive fluency of the memory. However, this doesn’t mean that it is true; one study saw participants with Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory (HSAM) incorrectly recall seeing footage of United Flight 93, on September 11, 2001, hurtling into a field in Pennsylvania, despite no such footage of this incident existing i.e. those with exceptional memory skills can create and recall things that never occurred. In this article, I want to look at how our memories of violent encounters, and those of people who may have witnessed them, can be flawed, and how this could affect a claim of self-defense; along with measures we can take to mitigate this.

One of the issues with many misremembered events, is that they contain elements of truth that may appear to corroborate things that didn’t occur e.g. a witness may remember the clothes you were wearing during a violent confrontation, but not remember it was the other person who was shouting at you, and not the other way around, etc. This can make their incorrectly recalled memory seem credible because it contains facts that you have to agree with and can’t dispute. Memories are also subject to change, based on the memories of others, and if an incident is discussed over a period of time, then there is a strong possibility that a person’s memory of an event may be altered, to conform to the memories of those with whom they are sharing their recollections i.e. if a group of people who just witnessed a fight you were involved in, start sharing their accounts, contagion can occur, and a “new” memory, based on shared accounts, can be created. A study by Paterson and Kemp (2006), revealed that 86% of witnesses, had talked with other witnesses, about their memories and recollections of events, before talking to the police. This can lead to issues, with witnesses being unable to discern the source of their information and where their memories of events originate from. Over time and with natural memory decay, the source of a memory can easily be forgotten. Being exposed to inconsistent information after the event, can severely affect a witness’s memory of what they actually witnessed, causing them to introduce information/evidence that they didn’t in fact witness; and discount, or actively forget things that they did see, or even experience. In fact, studies have shown that co-witness discussions following a crime produces a greater amount of misinformation than any other source, including leading questions by investigators and media reports.

This Social Contagion is believed to occur, due to two main reasons: normative influence and informational influence. Normative influence, involves the cost-benefit analysis, of disagreeing with another person/witness e.g. we may fail to offer a correction, when we recognize a piece of misinformation, because the other person’s recollection of an event seems largely, if not wholly, accurate, and to disagree with them might cause offense. However, our silence and failure to correct, may be seen as our tacit approval of their account, and so their memory and version of events (including the inaccuracies) appear as if they have been confirmed by us. Normative influence, may also see witnesses, who talk with other witnesses, leave out details that they are unsure about, due to a fear of embarrassment. Over time, these details may become lost to the witness, because they continually exclude them from their narrative. Informational Influence, occurs when a witness, discussing an event/incident with another witness, compares the accuracy of their account, with that of the other person’s. If another person seems more confident in their recollection of a memory, or provides information that suggests they may have been better placed, to accurately witness an event or incident, it is likely that they will believe that person’s memory, rather than their own. Over time as an act of violence is discussed, dissected by those who witnessed it, there is a good chance that Social Contagion, will see memories converge and conform, until a single narrative has been created, and the original memory reconstructed.

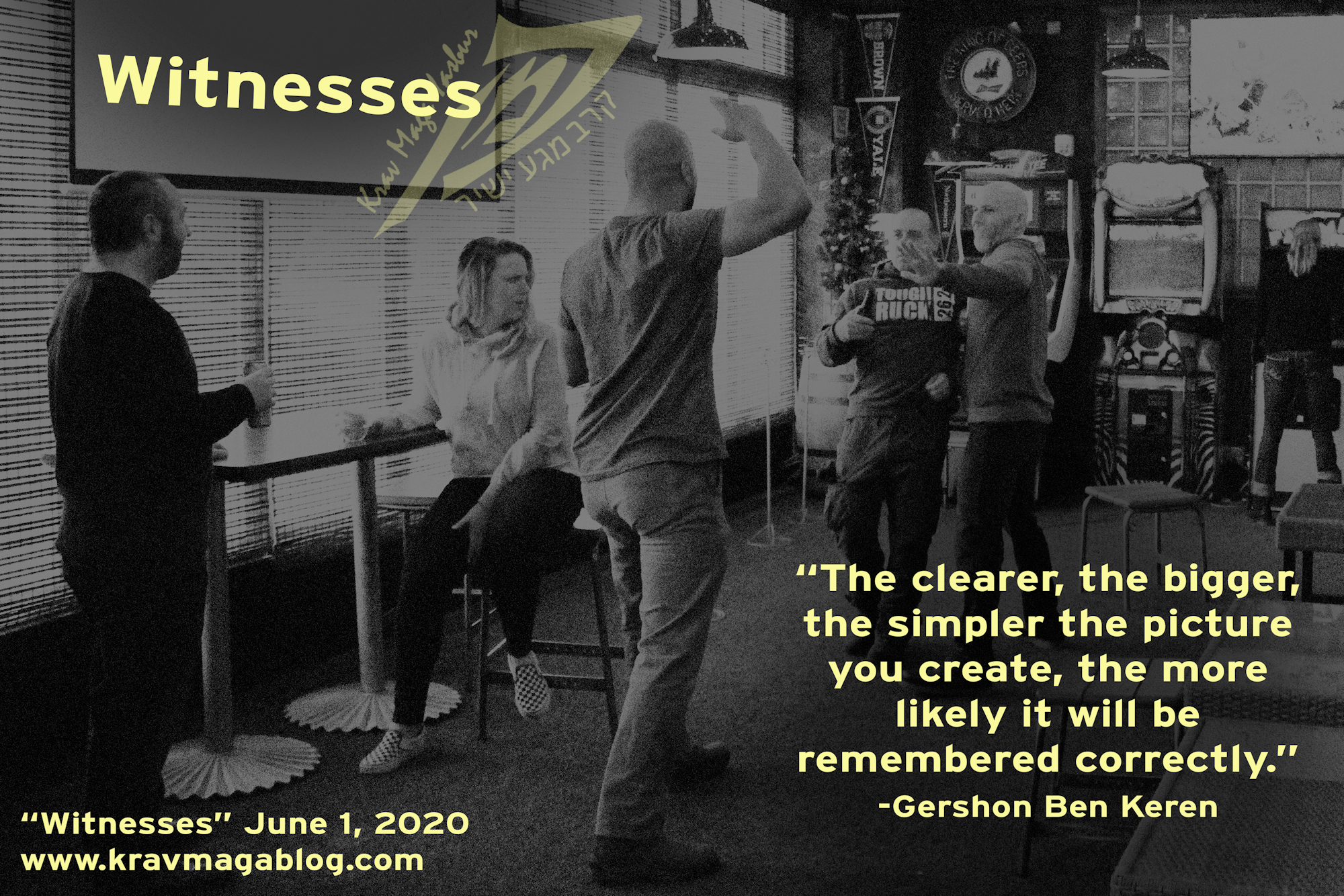

This is one of the reasons why it is important to plan on how you will act in the pre-conflict phase of an altercation, as you want to be able to present a simple narrative, that is obvious and easy for witnesses to remember, recall and articulate (these are three distinct stages in how memories are stored and recalled – every time you recall a memory, there is the opportunity to re-write it). This will involve drawing attention to yourself, which may be socially embarrassing, however it is important to “gather your witnesses” – an instruction I was given by a doorman, the first night I started working (CCTV wasn’t so present and available then, so you were extremely reliant on witnesses to corroborate your version of events if law-enforcement became involved). Stepping back, away from your assailant, with your arms out in front of you and telling the person to “Stay back!” is one way to create a clear picture of who the aggressor in the incident is – if they then move towards you, putting themselves in a position where they can make contact with you i.e. battery, they have now committed an assault – and you have the right to defend yourself. If your hands/arms are close to your body and not clearly visible, events may be remembered differently e.g. somebody may believe you were concealing a weapon, etc. somebody simply suggesting that you had something in your hand becomes an established fact, rather than simply conjecture. The clearer, the bigger, the simpler the picture you create, the more likely it will be remembered correctly. Our brains abhor ambiguities and will create facts to fill them; we don’t want to create this opportunity for witnesses whose evidence we may later rely on.