Author: Gershon Ben Keren

This is the first of three articles looking at crime hotspots in Boston, using Boston Police Department (BPD), incident reports (I’m using a dataset from 2015 to 2022). In this first article I want to look at the relationship between drug hotspots and robbery hotspots (those committed against individuals rather than commercial places). The second will look at property crime: theft/larceny against individuals, with the third looking at different types of auto-theft hotspots.

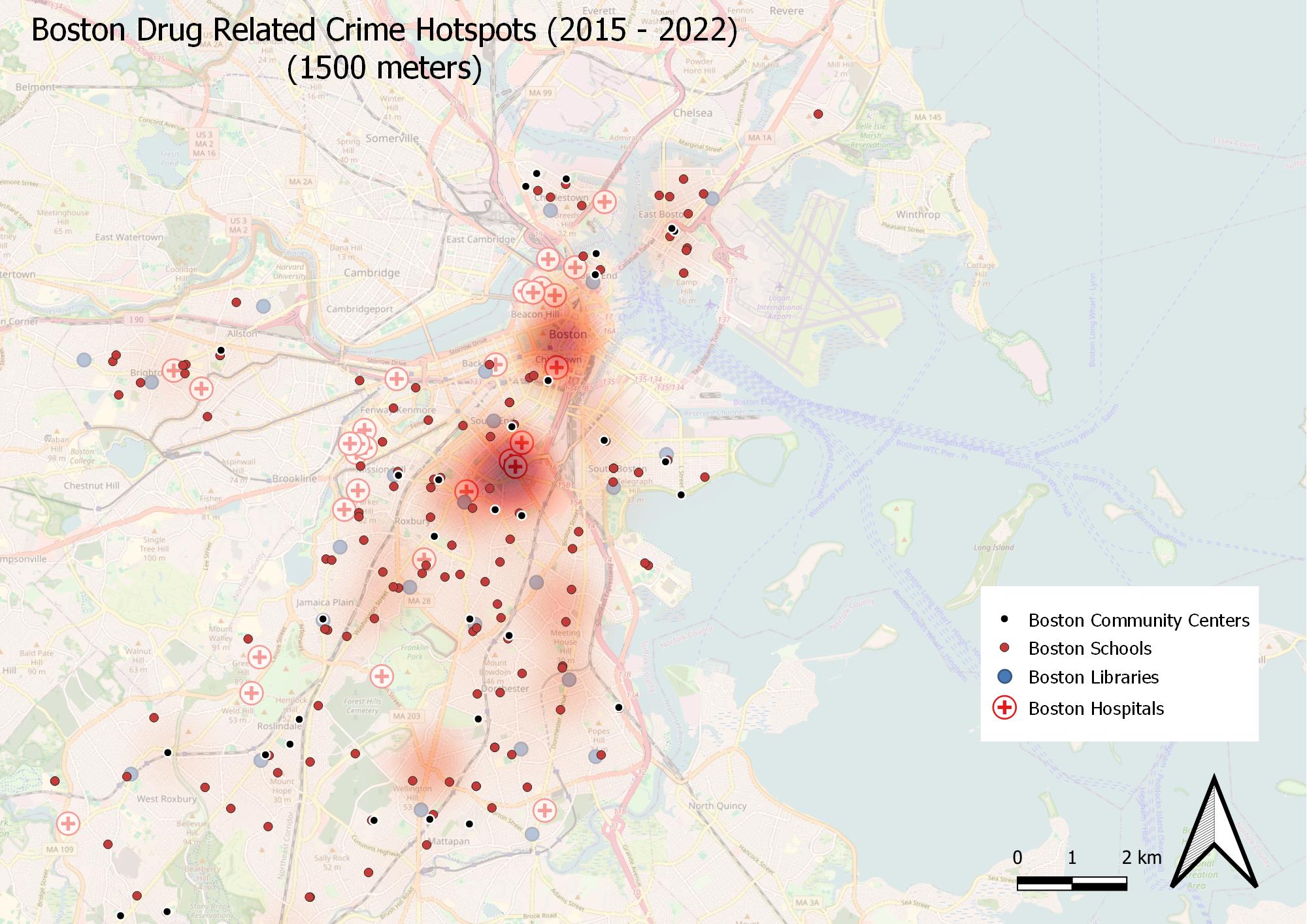

Boston's Drug Hotspots

When using incident reports to analyze crime hotspots, it’s important to recognize that some incidents are reported and other discovered e.g., an auto theft is likely to be reported by the owner, whereas a drug deal, is likely to be “discovered” by law enforcement. This difference also effects the statistics; most car owners will report the theft of a car in order to generate an incident report for insurance reasons, whereas a drug dealer is actively avoiding being caught and an incident report being generated. This is one of the reasons we can trust the true number of automobile thefts, far more than we can trust the true number of drug deals etc. It’s also why the numbers of auto theft are more likely to reflect the true nature of events than crimes such as robbery and petty theft, where those victimized, knowing that they’re unlikely to see their assets (property, cash, goods etc.) returned, decide not to report the crime e.g., having $30, stolen from you, and having to cancel your credit cards may not seem a serious enough event to warrant it being reported to law enforcement. When we look at incident reports that relate to “discovered” crimes, one of the things that needs to be considered is the number of officers patrolling an area, along with population density. This also highlights one of the issues with stop and search policies e.g., if we make an assumption that 10% of a city’s population uses illegal recreational drugs, and has possession of them at any particular time, and then look at a relatively small geographical area in the locale that houses 20% of the city’s population, if you initiate a stop and search policy, and compare it to a neighborhood that has 10% of the city’s population, then your stop and search policy is likely to be twice as “effective” when compared. If you then double the number of officers in that area who engage in stop and search, you double the “effectiveness” again. This is not to say that there isn’t merit, at times, for stopping and searching individuals, however it can become a self-fulfilling prophecy, where statistical success is seen as real success.

Boston has two very distinct drug hotspots, one in the city center, and one in the South End. It has long been understood that certain types of institutions and organizations have a certain gravitational effect on crime i.e., they draw those with a tendency to offend towards them. One such institution is trauma hospitals i.e., those that have busy emergency rooms. At the center of the “South End” is Boston Medical Center. This hospital is the largest and busiest provider of emergency services, not just in Boston or Massachusetts but in the whole of New England. Whilst there are clusters of other hospitals in the Fenway/Kenmore area and towards the north of the city around Beacon Hill, these don’t illicit the same type of pull, that those hospitals in the South End do. Those who use illegal drugs understand the risks they are taking and being close to an emergency room where they can quickly be treated increases their survival chances, it also means that there is a greater chance of medical staff being in the locale who may be carrying Narcan, an opioid overdose treatment. It has also been estimated that an emergency department which sees around 75 000 patient visits a year, can expect that around 262 of the monthly visits they receive will be from fabricating drug-seeking patients i.e., those making up/fabricating a reason in order to receive opioid/pain medication (Hansen, 2005); Boston Medical Center had 1,108,461 visits the previous year. Where there are addicts, there will be dealers.

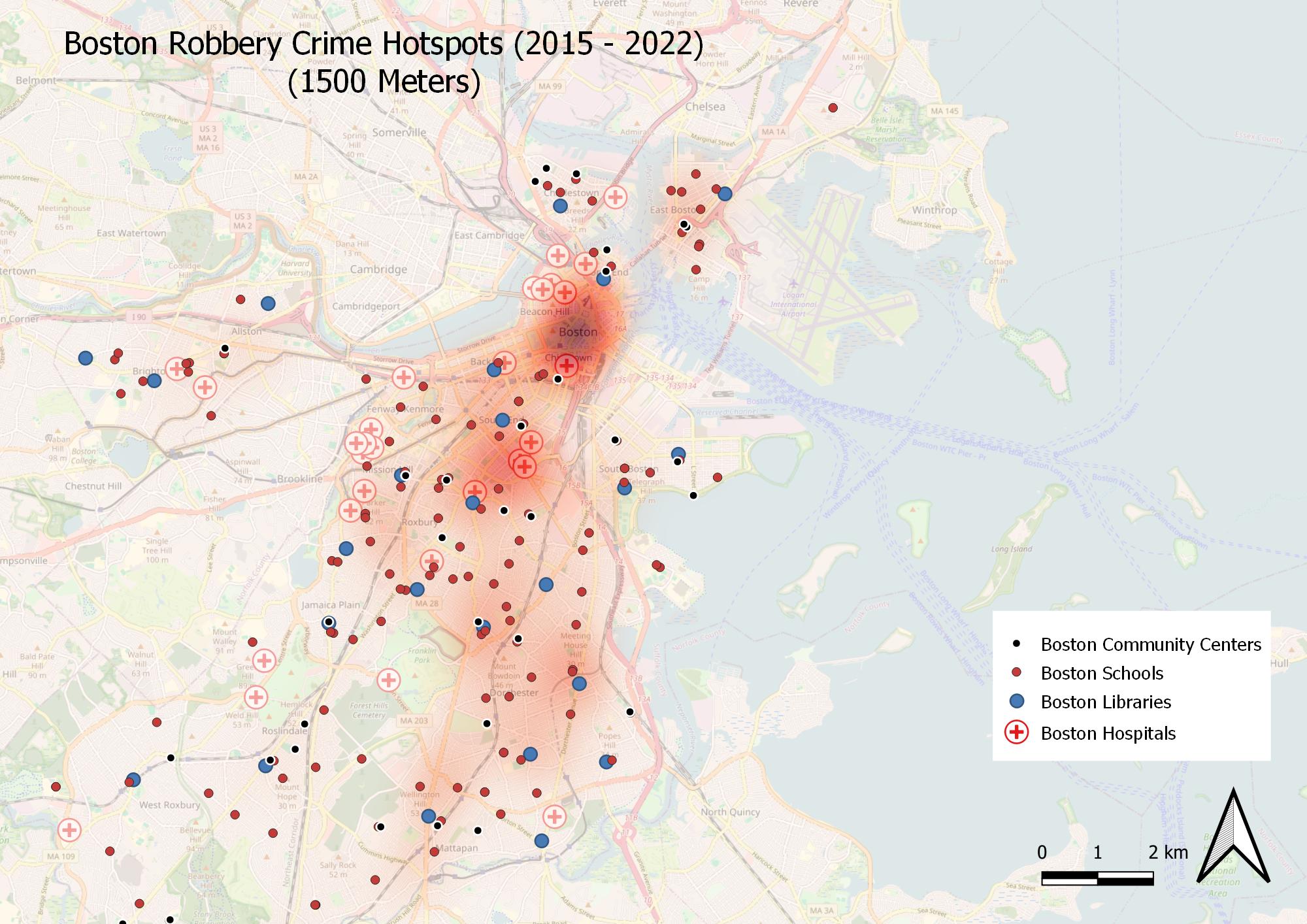

Boston's Robbery Hotspots

Boston’s drug hotspots are also its robbery hotspots – at the meso level i.e., this doesn’t mean that it contains Boston’s most prolific street segments and intersections, but rather that it contains the highest concentration, at a “neighborhood” level. The South End area, around the Boston Medical Center, is an area where statistically you are likely to be robbed at the same rate as its city center. Whilst the city center attracts significantly more people to it, BMC (Boston Medical Center) and its surrounding hospitals generate enough foot traffic, that it attracts both enough potential legitimate targets and motivated offenders, for it to create a hotspot. It is worth noting that some of those who commit robbery offenses may be visiting the hospital for legitimate reasons, and during the time they spend in and around the hospital, may find/spot offending opportunities. Such locations may also become areas of repeat victimization for those who work in these locations e.g., if you are a nurse, member of the maintenance team etc., you may regularly find yourself in the same location, at the same time, over, and over again. If there is a persistent offender who also finds that they share this space with you, because of their routine(s), the first time they victimize you may not be the last. Whilst too much emphasis is put on varying routes for safety etc., once you have been targeted it is worth attempting to avoid being in that location, at that time again. Once you have been victimized, changing routes and routines is worth doing; not so much as to appear “random” but so as to avoid re-victimization.

Next week’s article will look at auto theft, how certain areas of Boston are hotspots for this type of offense, and how there are different hotspots for the theft of automobiles and motorbikes i.e., they are distinct and different. The article will also look at how theft and robbery differ by geography.