Author: Gershon Ben Keren

Often when we look at the issues, problems, and complexities of multiple assailant scenarios, we look at such incidents from our own perspective, rather than from that of the group that we are facing. This is both natural, and understandable. However, if we can understand the dynamics of the group, the relationships between its members, and the different roles they may play/adopt, we may be able to enhance and improve our tactical responses to such scenarios. Whilst our physical tactics, might tell us to operate in one way, our “social tactics” may suggest a better and more effective way. It is important when looking at fighting concepts and principles for dealing with multiple attackers - such as lining attackers up, moving to the group’s flanks, etc. - that we don’t just blindly apply them, but fit them into the context of the situation we are dealing with; sometimes we can find that doing the “right” thing, is in fact wrong, because of the situational components present in the conflict. Every situation is different, and principles should guide our responses rather than define them. In real-life situations, many principles are heuristics (rules of thumb), rather than hard-and-fast rules.

Just as with one-on-one situations, the first question you must ask yourself, is whether this is a premeditated conflict, or one that has occurred spontaneously i.e. did the group plan the incident, or did they become involved organically, because of something you said or did, to one of its members e.g. such as knocking into one of them, inadvertently looking at them for too long, etc.? There is a big difference between a group, that is actively working together, and who has planned and orchestrated their interaction with you, and a group that forms around one of its members after an injustice, real or perceived, has been committed against them. In a premeditated multiple assailant confrontation, group members have likely been assigned roles, and are working to some form of script. In a spontaneous incident, members are working individually and to their own agendas/understanding of the situation. If the group has a collective experience of violence, informal roles may be adopted by members, based on past events e.g. the group may know who the fighters and aggressors are amongst them, who will do the talking and who will stay quiet, etc.

In a truly spontaneous situation, it should be the “wronged” party who will do the majority of the talking - if another member of the group takes up their cause, and they step back, there is the strong possibility that the group has been in this type of situation before and are working to an informal script (or even a ritual if this type of incident has occurred repeatedly), which sees one member adopt the role of the primary assailant. In a premeditated situation, the person doing the majority of the talking may not be the primary aggressor, and instead be a decoy who is there to draw your attention away from them, as they position and ready themselves to initiate the attack – that will see the rest of the group follow. In a few situations, such pre-conflict phases may be less defined, and you may find yourself having to physically defend yourself from an angry mob/gang who attacks you with little/no warning, however these types of assault are not the norm, and in most incidents any physical attack will be preceded by some form of dialogue. Being able to differentiate between someone playing the role of the “trigger”, and the primary assailant, is key to surviving such multiple attacker scenarios.

It is generally advisable to try to “target” the primary assailant, as they are the one who will want to be involved in the actual “conflict” phase of the fight, with other members being more reluctant to get involved. Trying to nullify this individual first, is often the best strategy, even if they may be in a position that would compromise a “physical strategy”, such as remaining in a central position, where you wouldn’t be able to line up other attackers behind them, and/or move/position yourself on the flanks of the groups. Just as Russian Snipers in Stalingrad during WWII, were taught to take out German Officers, because it would reduce the leadership capabilities of the German Army and offensive, taking out the primary assailant in a group will do much the same thing with the group. Not every member of the group has the same role or capabilities, and removing the primary assailant deprives the group of its most important asset.

It is unlikely that every member of a group is committed to violence, in the same way, and at the same level, as each other – this doesn’t mean that they aren’t still capable of extreme forms of violence (in the murder of Jamie Bulger, although both Venables and Thompson committed atrocious and despicable acts, it was Thompson who appeared as the accomplice rather than the driving force i.e. although both were able to commit torturous acts, it was Venables that displayed more of the appetite to do so – the torture and murder of Jamie Bulger by two ten years-old boys, should act as a reminder that children can commit extremely heinous criminal acts, and whose creativity and need to examine and explore the boundaries of human pain and suffering, can rival that of an adult) but that they may be reluctant to act, unless somebody else initiates the attack. I have seen, on several occasions, members of groups hang back, unwilling to get involved, until the individual being targeted is unable to fight back, and at that point they become some of the most enthusiastic participants – social diffusion reduces their individual responsibilities/culpabilities and frees them to act in a more extreme form than they would if they were on their own. If the primary assailant can quickly be shown to be vulnerable, susceptible to pain, and their abilities called into question, such individuals may find themselves less committed to the assault. By pre-emptively biting the nose, ripping the eyes from a primary assailant’s face, a strong message of deterrence can be shown/demonstrated to others in the group.

These individuals have a relationship with the primary aggressor, and whilst their role may be to support them during an assault, it is certainly not to replace them as the major attacker. Groups have hierarchies, and individuals adopt roles within those hierarchies. Most violent acts by groups, should reinforce, not question or challenge, those roles, or positions – unless there are those in the hierarchy who want to challenge those above them, etc. - something which is more prevalent in premeditated incidents of violence than in spontaneous ones.

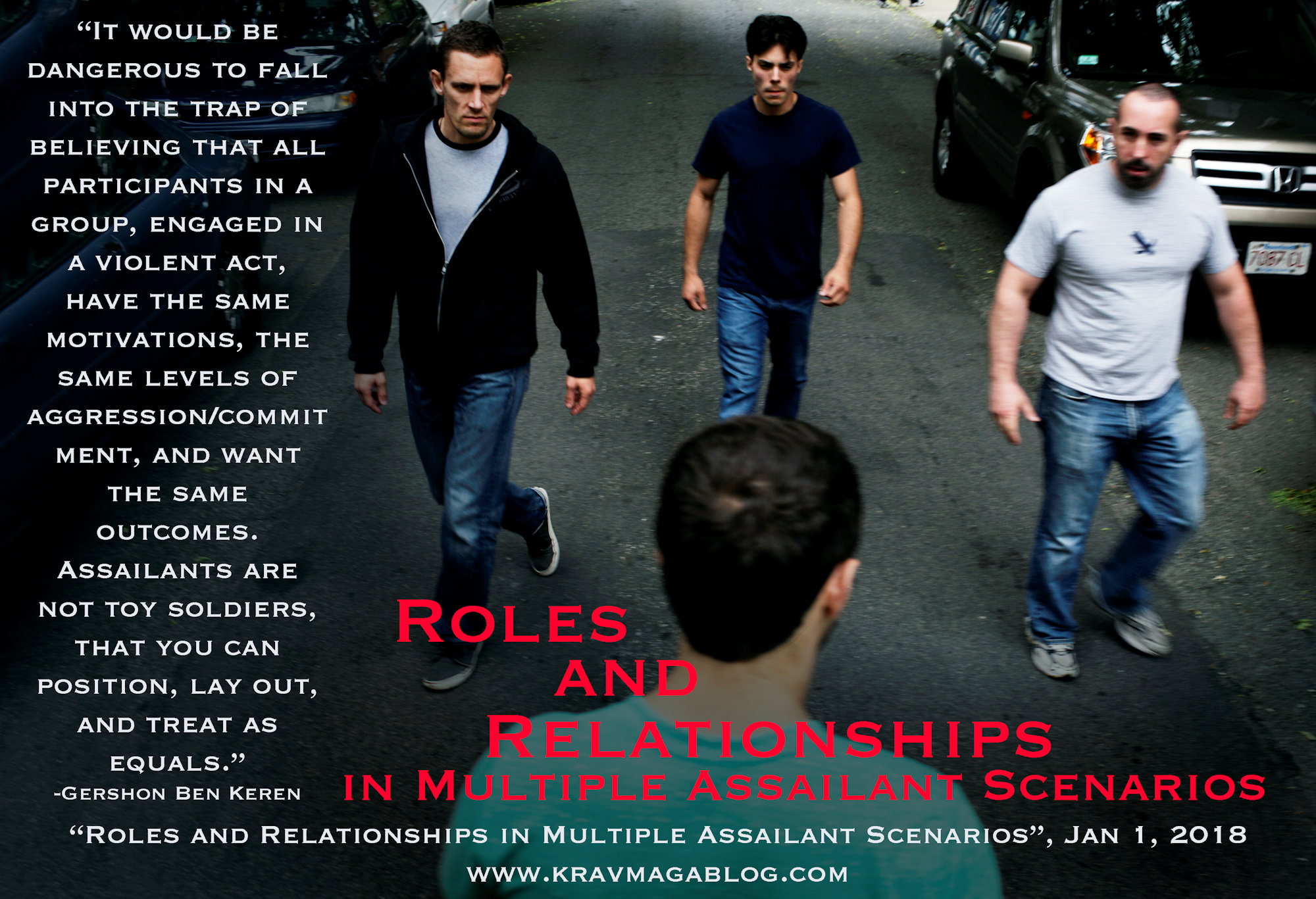

It would be dangerous to fall into the trap of believing that all participants in a group, engaged in a violent act, have the same motivations, the same levels of aggression/commitment, and want the same outcomes. Assailants are not toy soldiers, that you can position, lay out, and treat as equals. To do so is reducing each attacker to merely be person1, person2, person3, etc., when in truth person2 and person3 may have no desire to be involved in the fight. When a Field Marshall lays out his battle plan against an enemy, it is not just their regiments’ numbers and resources that are considered, but also their reputation, commitment, and resolve, etc. Our approach to dealing with multiple assailant situations should be the same; that we recognize each individual in the group for who they are, and devise our strategy for dealing with them accordingly.