Author: Gershon Ben Keren

Violence can be broken down into two subgroups: premeditated acts, where a motivated individual uses aggression, and potentially violence, to achieve a goal, and spontaneous acts where an unmotivated individual becomes motivated to use aggression and violence due to some event that occurs in their environment. Premeditated acts, include instrumental acts of aggression, such as offenders who engage in street robberies using the threat of violence to force a target to acquiesce to their demands, along with assertive and reassurance violence that is used by sexual predators, in their crimes. Spontaneous acts of violence can involve mis-readings of intent e.g. “are you looking at my girlfriend/boyfriend?”, or be caused by “automatic” reactions and responses to things such as being knocked/bumped into, etc. In this article, I want to look at why some people become aggressive and potentially violent, when genuinely non-threatening and non-challenging things happen to them, and why others are able to recognize the lack of harmful intent behind an action/behavior and are able to shrug and/or laugh it off. By understanding the different “routes” by which people acquire information, we can better understand the causes of aggression and violence in spontaneous situations.

We acquire and process information about our environment, using three different methods/routes; and in certain situations, one may take precedence over another, effectively hi-jacking the way we make assessments about what is happening to us. These three routes can basically be looked on as being: cognitive, affective and arousal. When an event, such as somebody accidentally spilling a drink over us occurs, we will try to cognitively process what has happened to us, in order to determine how we should respond (this is in the appraisal phase). According to our behavioral scripts, that we have developed over time, we may see what has happened to us as a direct or indirect challenge to our identity and status. A direct challenge would be one where we believe the individual spilt the drink deliberately in order to judge our response, and determine whether they are above us in the pecking order or not, where an indirect challenge would be one, where we understand the spilling of the drink was an accident, however we’re concerned how others may judge our status in the pecking order by the way we respond, or don’t respond, etc. For most of us, we may be annoyed at what has happened, with our scripts telling us that “accidents happen”, and that no challenge or threat is present; for others, their scripts may tell them otherwise and that they need to respond physically in order to maintain both their internal and external reputation. These are the individuals who are predisposed to use violence as a solution to socially awkward and difficult situations. Our cognitive understanding of an incident can also influence our affective and arousal states (they work interdependently) e.g. thinking about an injustice, such as having a drink spilt over us, can increase our state of arousal, making us more angry, which in turn affects the way we think about the incident, etc.

Arousal can also be affected independently e.g. it is well documented that both heat and alcohol can increase our state of arousal, etc. Anyone who has worked door and bar security in the UK knows that the first hot/sunny Saturday, after winter, is a nightmare. As soon as the pubs open, people will go to the beer garden – to enjoy the fact that they can be outdoors – and start drinking. This will go on over the course of the day, with many people getting sunburnt; and then drunk and over-heated, they’ll stumble into the city in the evening to continue their revelries, primed to take offense at any perceived slight or injustice due to their heightened state of physical arousal. Pain will also heighten a person’s state of arousal, so stepping on somebody’s foot and/or knocking into them, will similarly have an affect; couple this with the fact that a person is sunburnt and drunk, and the pieces are all there for a violent outburst. Input variables such as personal insults will create hostile moods and alter our affective state/path. Sometimes we don’t realize that what we are saying may be deemed as insulting e.g. telling somebody to get over it because it was just an accident, will be deemed as dismissive, as will your frustration at the way the situation is going, that probably caused you to make the remark. Cognitive, arousal and affective pathways will all influence how an individual both initially appraises the situation, along with their reappraisal of it.

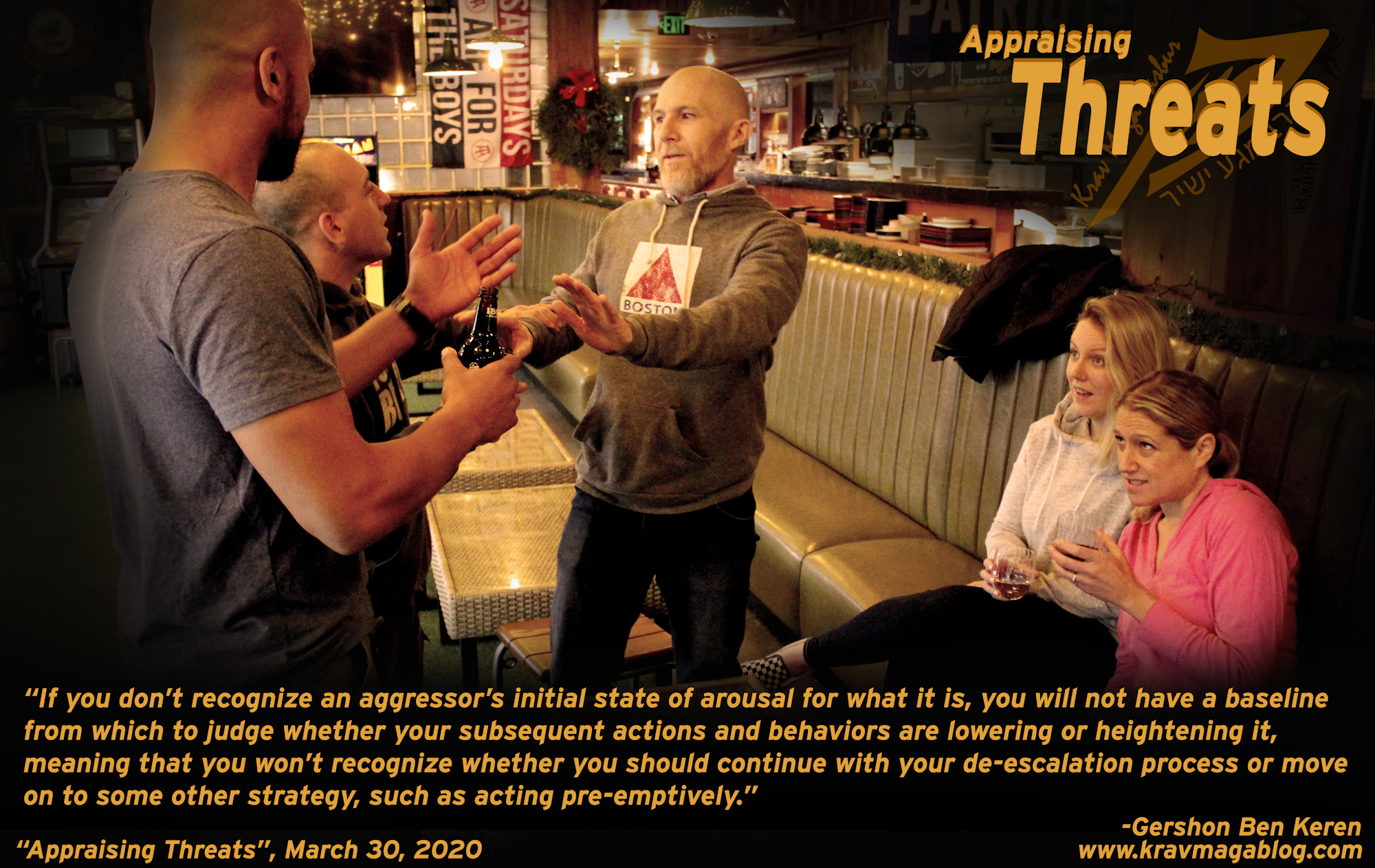

It is during the reappraisal phase of the interaction, that an aggressor considers their alternatives, their ability to act violently, and the consequences of their potential actions. Although this may seem a purely cognitive process, in a heightened state of affect and arousal, more basic and primal scripts are likely to be running. Other species are very good at immediately recognizing arousal in their members, humans are not. In fact, we’re very bad at it, and will often interpret another’s aroused state incorrectly, not recognizing that we need to do something to lower and reduce it. There is a real danger of going into a situation believing that the person you are dealing with is in the same state of arousal and affect as yourself. If you don’t recognize an aggressor’s initial state of arousal for what it is, you will not have a baseline from which to judge whether your subsequent actions and behaviors are lowering or heightening it, meaning that you won’t recognize whether you should continue with your de-escalation process or move on to some other strategy, such as acting pre-emptively.