Author: Gershon Ben Keren

In last week’s article, I looked at some of the reasons why people are reluctant to act, when they are presented with a threat or danger. This reluctance, is very different to “freezing”, which is largely an emotional response, rather than a psychological one. Reluctance, is much more akin to the denial and discounting of the danger, and the deliberation involved in reaching a decision, as to how to deal with the threat, than the physical inability to respond i.e. freezing. This is not to say that the two won’t occur in tandem, just that the methods to overcome a reluctance to act, are somewhat different to those used to move out of the freeze state – though they will assist in this, where there is a physical component to them.

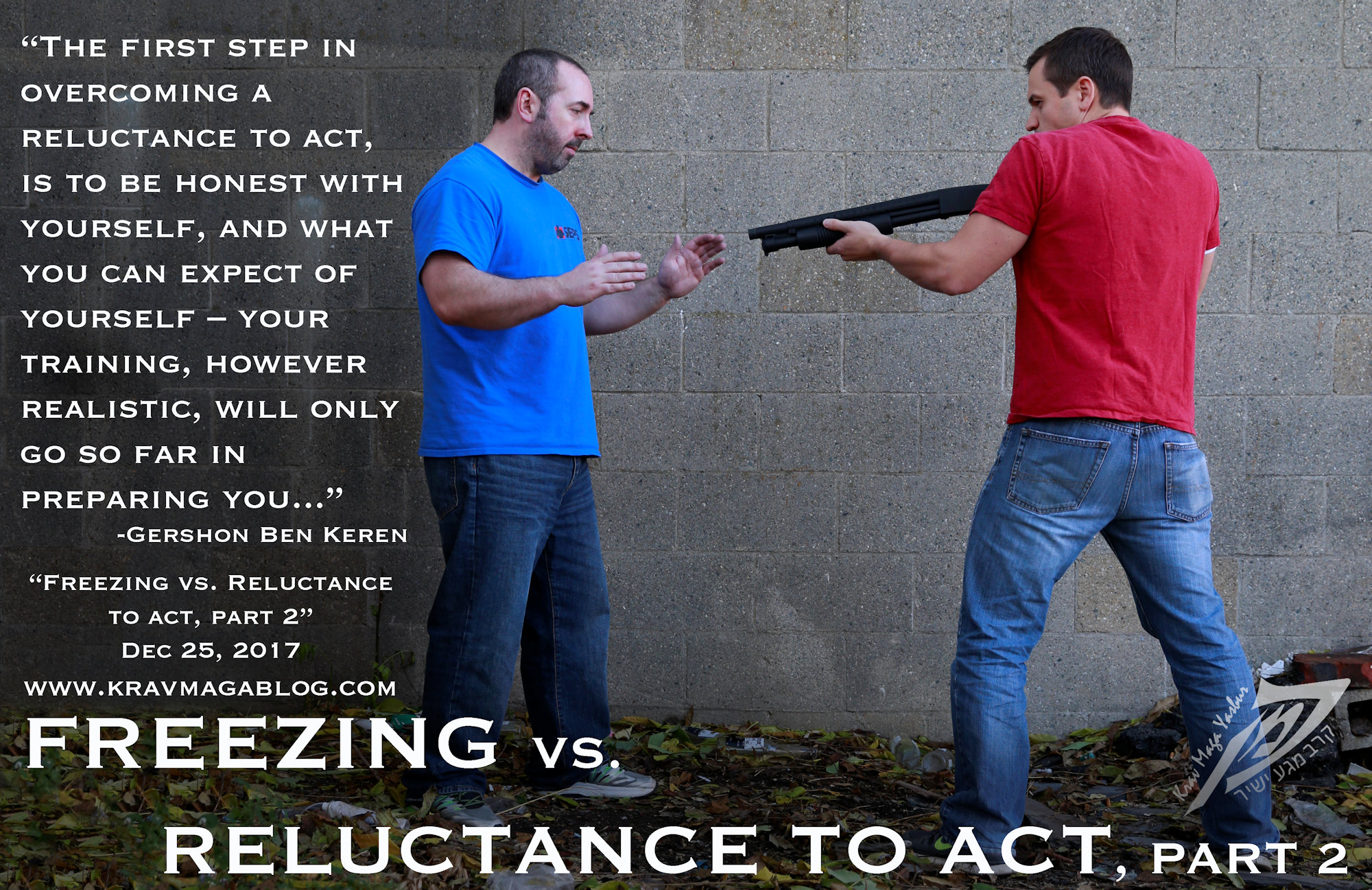

The first step in overcoming a reluctance to act, is to be honest with yourself, and what you can expect of yourself – your training, however realistic, will only go so far in preparing you; this is not a criticism of anybody’s training methods, just that the reality of a committed attacker coming at you with a knife, etc. can’t be fully replicated in a gym or studio setting, unless a real knife is used, and the attacker is given the remit to do everything that they can to repeatedly stab you, until you can’t fight back anymore, etc. shock knives and other training tools are great, and extend the reach and reality, of the training environment, however you will still know that you’re going home at the end of the session (and this underlying knowledge and assumption will influence your response and reaction to the danger). Don’t be blasé, about what you believe you would do in a particular situation, and how you would react, as this may mean that you won’t recognize your reluctance to act, when facing someone who is dedicated to causing you serious harm/injury. None of us are perfect, and none of us will react/respond perfectly in every situation. However “good” we believe ourselves to be, we must recognize this, so that we can overcome this “reluctance” if we experience it.

Often, we must “force” ourselves to act. I wrote in the last article about our natural/in-built reluctance to do anything to change a situation in which we are not yet experiencing pain, and in which the consequence of acting could result in pain e.g. if you are facing an aggressor who is spitting, screaming, and shouting threats as they move towards you, you “know” that your survival chances will likely increase if you act pre-emptively. The problem is that, this could cause your attacker to respond by attempting to inflict pain on you; ironically, what they are intending to do to you anyway. One way to overcome this natural reluctance, is to have processes and procedures that you run through, which force you to act. One that I adopt when dealing with verbally aggressive individuals, is to step back and raise my hands (adopting a De-escalation Stance), and ask a pre-set, open-ended question. If my assailant steps towards me, I attack. I have a pre-built opening combination, and after that, the situation, my attacker’s responses/movements, etc. will dictate my striking patterns. I only ever prepare for the first few moments of the conflict phase, and after that it is the “training” that takes over. My initial response/decision to act though, is based on my attacker’s response: their movement/step towards me - it is this, which forces me to act. I have several of these simple scripts that I work to, and they help me overcome any hesitation and doubts that I may have about responding physically.

The “when” of responding, is as important as the “how”, although this often gets neglected in training e.g. if you are going to attempt to disarm somebody of a knife or gun, when do you do it? Do you always attempt to control the weapon as soon as you see it? Do you wait until the person makes a request (such as for you to move, hand over your wallet, etc.), and make a judgment to act based on this? It is worth remembering that situations determine solutions, and not the other way around. There may be times that you should look to control a weapon immediately – when you believe that it is going to be used straight away, in some assassination attempt – but there may also be times that you may not see, or be aware of, the weapon, until you hear an assailant’s demands, etc. If you are not looking to spoil the draw, have a response that sets off a chain of events. Putting your hands up, when a weapon is aimed at your head, etc. is a good physical response, if mental processes are attached to it, and it’s not simply a “passive” response to the threat. Have a pre-built decision tree, that dictates if/when you will attempt to control/disarm them off their weapon e.g. if they demand that you move, if they remain after you’ve handed over your resources, etc. – these pre-built responses/decisions, will help you overcome any natural reluctance, you may have to act. Be aware that you will only be able to hold a couple of thoughts in your head, under the stress and duress of the situation. Attempting to think about too many things that you have to do will keep you in a state of indecision, and hesitation. Just as I only think about the initial strike I’ll make when acting pre-emptively, I do a similar thing when dealing with weapon threats. I will have a “mantra” that I recite, such as “Move the weapon, move the body”, that I repeat in my mind – two simple things, which will give me a hand-defense and a body-defense (basic Krav Maga principles). When I act, this should get me past the most crucial stage of the defense, and allow me an opportunity for my training to take over.

I also use the syllables in sentences I may say, as points to force me to act. If I’m dealing with an armed mugger who has taken my wallet and/or other resources, I may say to them, “Is there anything else you want?” As soon as a question is started e.g. “Is there…” an individual will start to mentally fill in the rest of the sentence, before it’s been said (this is the same phenomena as reading ahead in a book, where we start to process sentences before we have fully read them). This will distract them from whatever task they were planning next, which may involve using the weapon against me. However, my intention is not to complete the sentence, but force myself to start my solution/technique, on the third syllable (“Is there any…”). This is like counting, 1,2,3 before jumping out of a plane, or off a platform when doing a bungee jump, etc. When we have to overcome a fear, forcing ourselves to act on a particular count, helps us overcome our reluctance. Having a sentence/statement/question that you make to an aggressor, with a syllable, such as the third (1,2,3), that you use to force yourself to act is a great aid to decisiveness; one of the most important self-protection and self-defense skills we can have.

Just as we train – or should train – to overcome the freeze response, so we should also train to overcome our reluctance(s) to act. Just as we can talk ourselves out of acting, we should be able to self-talk ourselves into responding. Creating and having scripts and processes that we use to do so, is an important part of our training. Visualization is also a key tool to helping us overcome our reluctance to act, and this is something I have written about extensively (you can use the search functions on the Krav Maga Blog page, to find articles about this). Whilst physical techniques need to be practiced, these are only one part of any solution to violence, and we need to have everything in place that will allow them to work, if we are to be successful in dealing with real-life violence.