Author: Gershon Ben Keren

Last Autumn, I went back to school to do a second Master’s. It had been over 20-years since I’d been in academia, and I needed to both broaden and update my perspectives. My self-study approach to both psychology and criminology, had run its course, and I was in a situation where I didn’t know, what I didn’t know. I wanted to engage in thinking critically about what I already knew; as well as learn things I didn’t. This is something that is encouraged in academic circles (my professors don’t want me to read only one opinion), but which is often avoided within the martial arts – one exception being competitive martial arts, such as MMA, where any new perspective, idea or approach could give somebody the edge when they compete. In reality-based martial arts and self-defense, this critical thinking, is only applied by those who truly expect to have to deal with real-life situations. Those who don’t believe it will ever happen, can afford to engage in cult-like thinking, where they only have to think about how they would fit – sometimes shoe-horning in - their current approach and way of thinking i.e. what their system tells them to do, into their idea of reality. In certain cases, they have to alter reality to do this, so that what their solution “works” e.g. they create in training more time and space for themselves, than is actually present in a real-life conflict to react and respond, and/or they don’t recoil the knife or the punch, to enable them to control it, etc. In this article I want to look at the dangers of cult-like thinking, and why we should apply critical-thinking to that which we teach.

Cult-like thinking promotes idealism over realism; whereas critical thinking acknowledges that a one size fits all approach, isn’t applicable or effective in every situation. I prefer to use the term ‘heuristics’ to describe what many others refer to as ‘principles’ – but if people prefer to use the term ‘principles’ to determine the approach they take, we still need to acknowledge that reality has enough grey areas, that these can’t always be followed to the letter, or applied as hard-and-fast rules to every situation. Appropriate responses to violence, are governed by the context of the situation i.e. situations determine solutions and not the other way around. There are concepts and ideas that can guide and direct us, but these should never be seen as principles that we must follow at all costs; it is cult-like thinking that would tell us, or prescribe, that we should always respond to a situation in a certain way. Critical thinking allows us to see many ways to respond and allows us to determine which one(s) will be effective and appropriate, given the context of the situation we are dealing with. A system, such as Krav Maga, should direct our responses, rather than dictate them e.g. there will be times to combatively shut down an armed attacker before we control the weapon, as well as times when we should control the weapon before we shut them down; and there might be times when we disengage, instead of shutting the attacker down, etc. Violence is fluid, and subject to context, and it is this that determines what we “should” do.

Perhaps the biggest issue with cult-like thinking, is that someone or something must be wrong, for it to be right i.e. it’s not able to acknowledge that a contrary opinion to its own can be right, for different reasons to its own. This comes partly from an inability to understand the importance of context, and partly from an insecurity, that sees its viewpoint and opinion as having to be right, and everyone else’s as wrong. During my time in the martial arts, and Krav Maga, I have been taught several different ways to throw a roundhouse kick, along with different methods of throwing back and side-kicks, etc. Cult-like thinking says that only one of these methods can be right, critical thinking on the other hand, says they can all be right, and in fact each one may have strengths (as well as weaknesses) that the others don’t. My background is predominately in the Japanese Martial Arts, but I have spent a little time studying Korean Martial Arts – in certain instances similar kicks are executed differently e.g. sometimes a kick is chambered to generate power, in other instances it is “lifted” to gain power. Which is right? Both are, context dictates: sometimes you need power over speed, and sometimes it’s the other way around. If you don’t understand both approaches though, you’ll always assume that the other party has got it wrong. In cult-like thinking, one must be “wrong”, to make the other “right”.

In conflict resolution terms, we refer to this as a competitive-conflict, where there must be a win-lose outcome, because the loss is as important as the win, to one of the parties. To put it another way, the goals of both parties are negatively independent as opposed to being positively interdependent. In a positively interdependent conflict, everybody wants a win/win outcome e.g. whichever kicking camp you are in, you want to educate the other party as to why you kick the way you do, and better understand why they kick the way they do, etc., recognizing that you might learn something new from them, and them from you etc. We refer to this as a co-operative conflict. Unfortunately, for those engaged in cult-like thinking, co-operation in a conflict, and learning from others outside their own circle, is anathema. Any conflict exists to prove they are right; they must win, and the other party must lose – with the loss being as important to them, as the win. Many people, when they first start working door security engage in this type of conflict resolution, which is really a type of enforcement. Instead of trying to get a person who needs to be ejected, to see that it’s better if they leave of their own volition (interdependent goals: they want to leave, you want them to leave, etc.), they feel the need to be the one that comes out on top, and wins the conflict, by making them leave i.e. making the other person lose in the conflict. The need to win, and to be right, usually leads in sub-optimal outcomes for all involved.

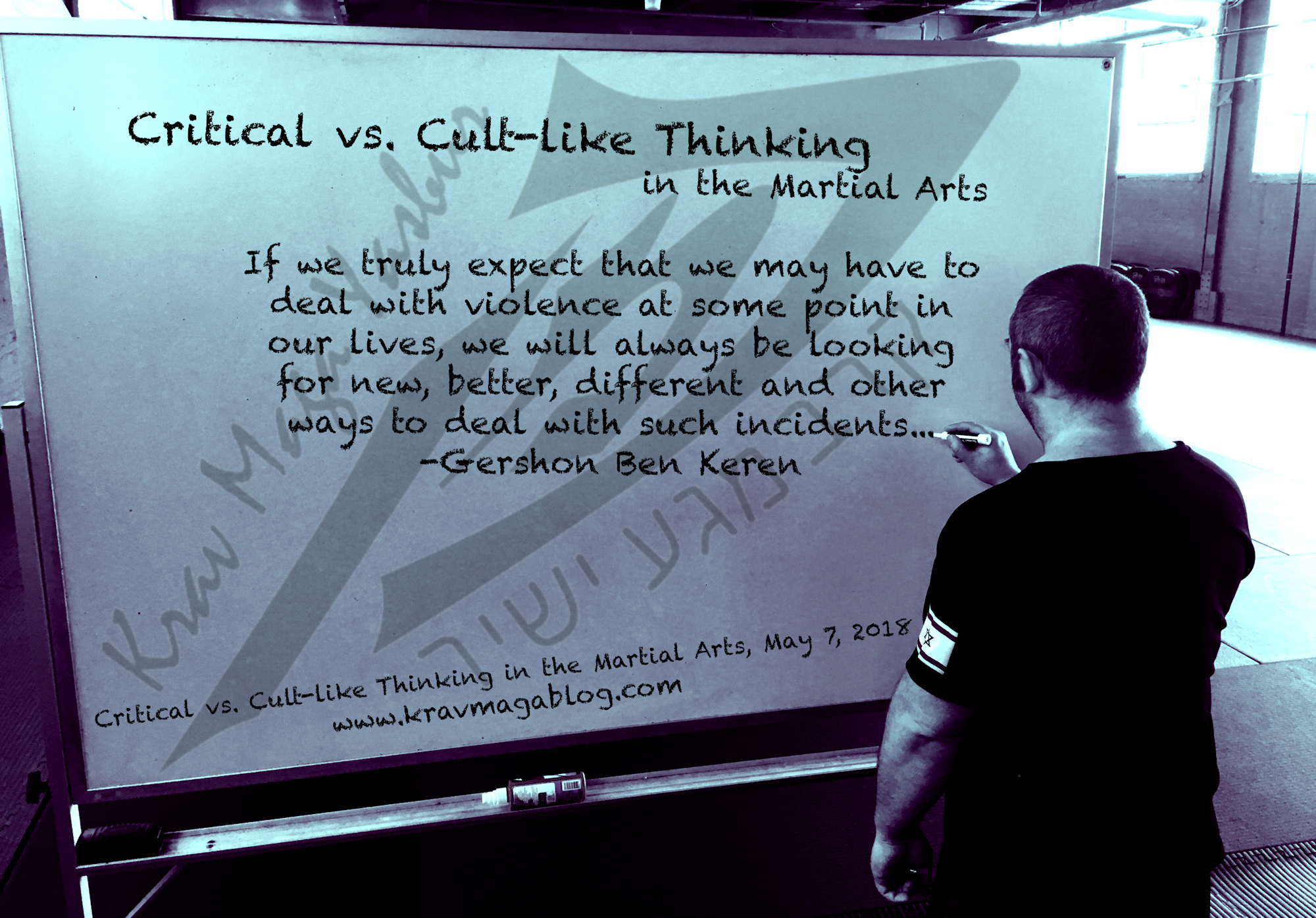

If we truly expect that we may have to deal with violence at some point in our lives, we will always be looking for new, better, different and other ways to deal with such incidents; this doesn’t mean we have to sacrifice our approach, but recognize where we may have gaps and weaknesses. I am constantly on the search for better ways to deal with knife attacks – I’m not happy with what I teach, but it’s the best way I have found to this moment. I train, talk with others, watch other system’s approaches, to better learn and understand, and see if what is being demonstrated works in the contexts I’m training for and/or has something to offer me. If it doesn’t, that doesn’t mean it is wrong, and neither do I feel the need to say so; I may simply not be aware of the context (context is king), or the reasons behind that approach i.e. it may be that we are both right, even though what we teach/propose may be different. Rather than cult-like thinking – where we view everything different as an attack that we must defend against – we should try to engage in critical thinking when seeking solutions to violence.