Author: Gershon Ben Keren

If you’ve ever leaned back in a chair, and found yourself on the wrong side of the tipping point, you will have experienced a moment of panic, where your only thoughts and actions would have involved trying to regain your balance. The same will be true if you find yourself slipping on ice, tripping over an object, or losing your footing in some other way. It doesn’t take much to lose your balance. The head weighs about 8 pounds, and doesn’t have to pass too far from over the shoulders and the hips, to take your body out of balance – if this happens rapidly, in an uncontrolled fashion, that feeling of panic, borne out of our natural fear of falling, takes over. We may be able to train our body to respond to this sensation, such as by going with the fall, and making a break-fall, etc., but we can’t switch our thought processes to something else.

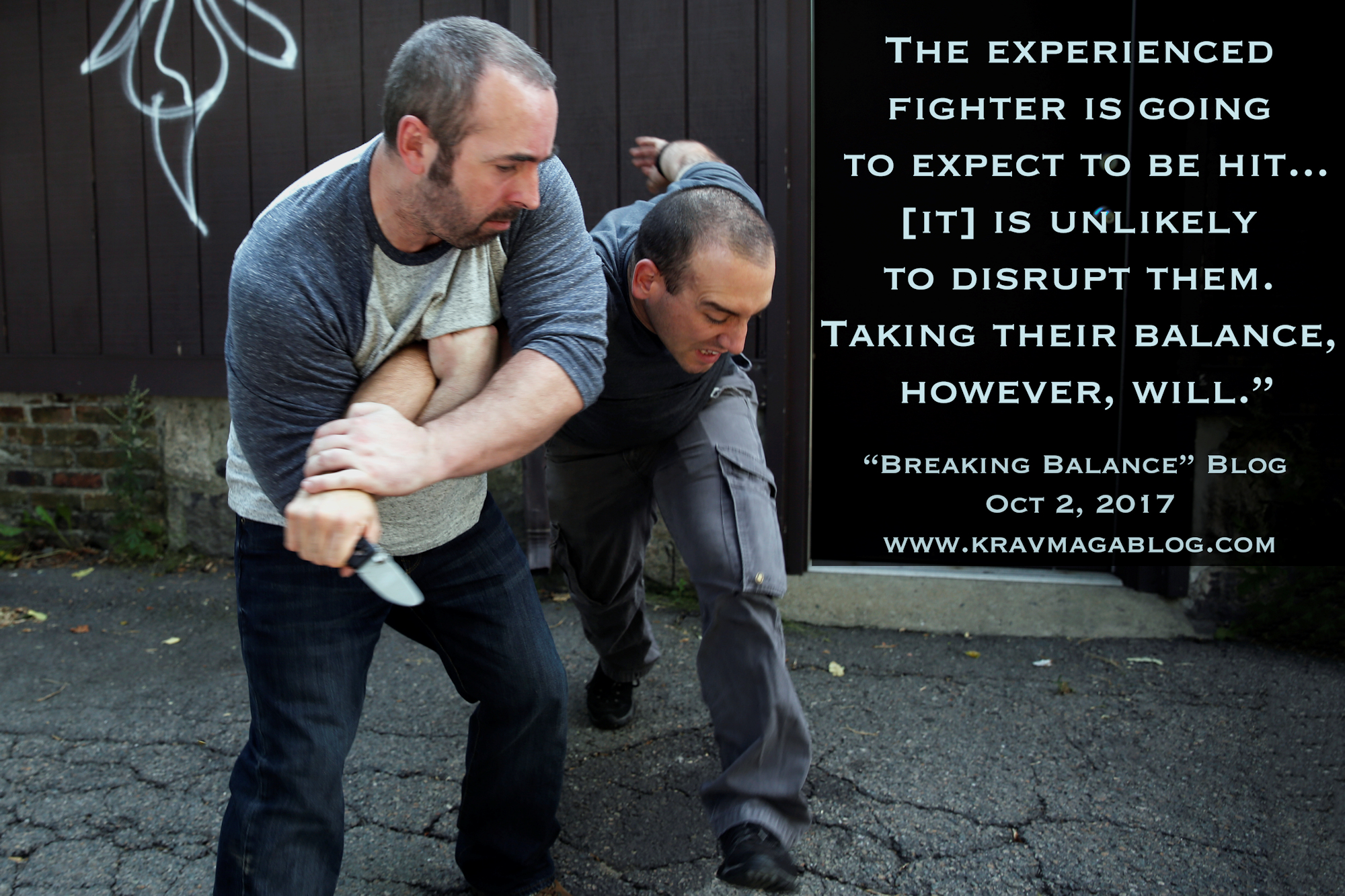

When we spar, or are involved in a fight, we can turn our pain management systems on, in order to control our experiences of pain – we can also condition ourselves to reduce the feeling of pain e.g. if you’ve never experienced the trauma caused by a roundhouse kick to the thigh, when it first happens the pain will be excruciating, but after several years of training and conditioning where you’ve experienced this type of pain over and over again, the effect will be lessened – you will know what to expect, and you will have learnt to manage it. If you have to deal with someone in a real-life confrontation, who has experienced many fights before, your striking is not going to have the same effect, as if you were going up against someone who’s never been in a fight. The experienced fighter is going to expect to be hit, and probably won’t care too much about it – the shock and surprise of being punched will have left them a long time ago, and if they’ve been drinking or taking drugs, being punched/kicked, etc., is unlikely to disrupt them. Taking their balance, however, will.

One of the most common initiating attacks I’ve seen, and experienced, is a hard push followed closely by a punch. Even the untrained attacker knows that whilst their target/victim is falling/moving backwards all their attention will be on trying to regain balance, and during this period they will not be in any position to make an adequate defense to the following strike/punch. Most fights are over in seconds, and the person initiating the attack is normally the successful one; if they can keep the other person off-balance and moving, it is unlikely that they will recover enough to both defend themselves adequately and respond with attacks of their own – most will emotionally crumble at this point and take themselves out of the fight. Taking balance is the key in delivering success to this type of assault. As martial artists, we may look down on these unsophisticated tactics, however we must ask ourselves why trained people often fall foul of them, and a large part of that answer is that we can’t train ourselves out of that moment when we first lose our balance. Even if we are experienced Aikidoka and Judoka, who once we recognize it, can respond, we are still vulnerable in that moment – and our focus goes to initiating the break-fall, not dealing with a follow up attack - this extremely short window is what the untrained but seasoned fighter is able to exploit (and we should learn to exploit it as well).

Using simple pushes, that take an assailant’s balance, can also help us position our assailant so that our strike, punch or kick is more effective from a power generation perspective. When pushed, a person will try to regain balance, by centering and attempting to root their weight. When they do this ,their legs become vulnerable to low kicks, as their weight will be loaded firmly on them. This can easily be trained and developed in sparring. A variation of this – that doesn’t involve taking balance – is to push yourself off an attacker, pressing their legs into the ground, as you move back and kick the legs. This is another way to make sure that weight is loaded onto the limb you are attacking.

Taking an attacker’s balance when you are disarming them of a weapon, is a good way to take their attention away from the knife, gun or stick they are holding. Disarming should not be a static process, it should involve moving the person, so that all their attention is directed towards them staying on their feet, and not on retaining their weapon. If this movement can be combined with lower-level combatives, such as knees and kicks, then all the better – arms and hands should be kept, controlling the weapon arm, and weapon. When a person is rag-dolled around like this, they are disorientated and focused on one thing only: regaining their balance. Attacking balance, should be put on the same par, as attacking with strikes and punches, and in reality, is often much more effective at disrupting an assailant’s assault, whether it is armed or unarmed.

Attacking balance is the first thing that should be done when attempting to throw or perform a takedown. Unfortunately, many people still see throwing somebody as an act of “lifting”, which requires strength, and this is not helped when videos and photos, show a throw being attempted on someone whose head is still over their shoulders, and their shoulders positioned over their hips, etc. This is why it is virtually impossible to throw someone who is punching with good form, as unless they are over-committing to the strike, their balance won’t have been disrupted – plus, if they are recoiling the punch, there is little to no chance of taking/grabbing hold of the arm. There are some very, very restricted instances in which throwing someone who is punching is possible, but it relies solely on their movement and them giving up their own balance. Balance taking, makes a throw effortless, because the person is already falling, and only requires being directed. This is a skill which takes time to develop, however it is one that allows a smaller person to overcome a much larger attacker, where there is a significant size and weight disadvantage e.g. a 110 LB individual, will be able to generate more power against a 250 LB person through throwing, than they would through punching/striking.

Balance taking doesn’t have to be as “sophisticated” as throwing, sweeping or reaping, but the tactical advantages it gives should be appreciated and understood. If we recognize that pushes followed by some form of attack, work well for untrained individuals in confrontations, we should look at ways we can incorporate and improve on them, in our own training. An individual is perhaps no more vulnerable when they have lost balance, and this is something we should use to our own advantage.