Author: Gershon Ben Keren

I have written in previous articles about how crime and violence (in Boston) changed during the strictest part of the COVID-19 lockdown (March-June 2020), based on police incident reports. However, with the first deliveries of the vaccine to the Boston Medical Community, it may be time to start looking at and imagining what the criminal landscape may start to look like as things return to “normal”. I would like to caveat what I write by stating that this isn’t a prediction, but more of a conservative and evidential speculation that doesn’t include a post-apocalyptic city with burning buildings and zombies walking the streets etc.

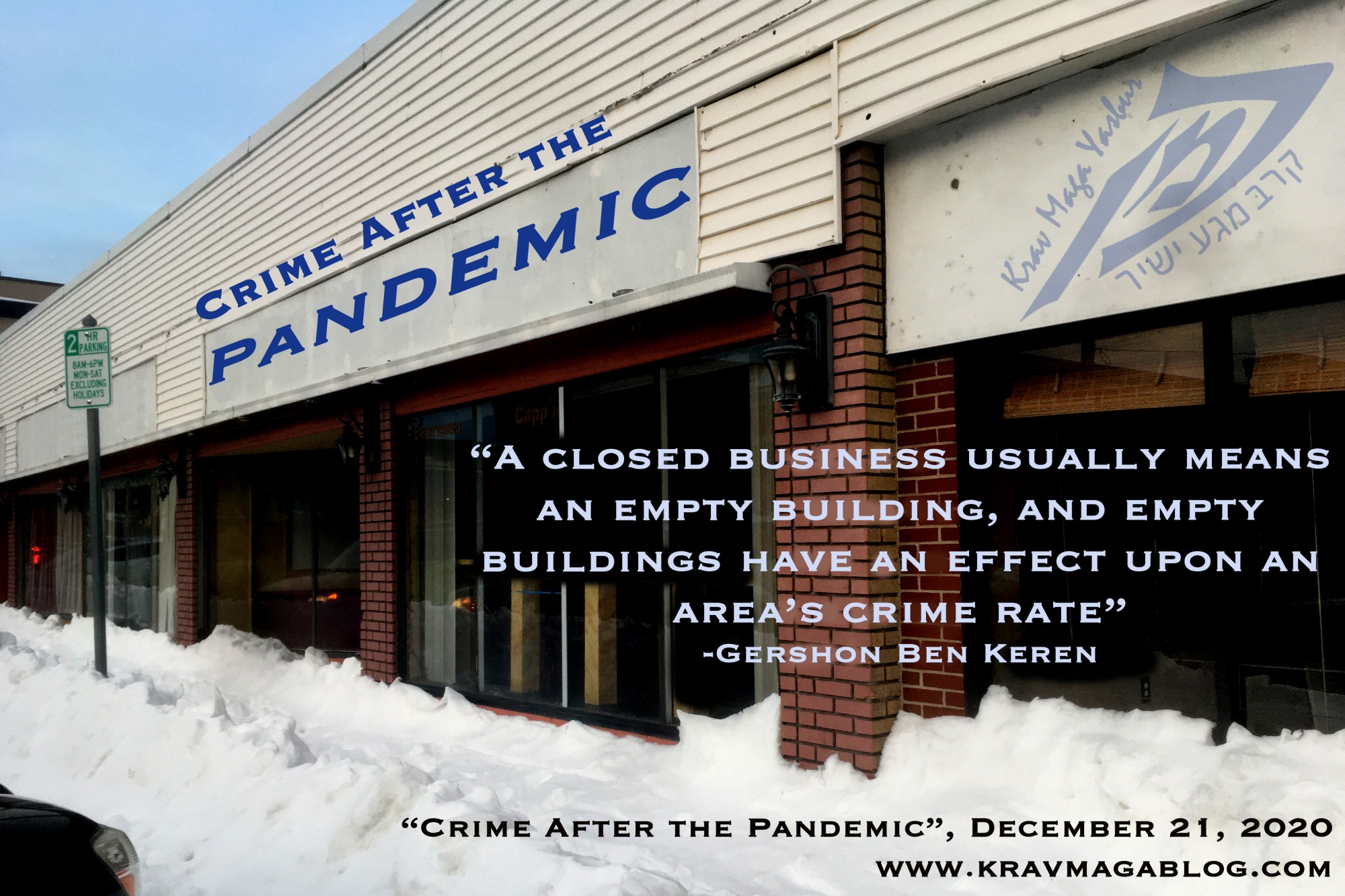

Perhaps one of the most long-lasting consequential effects of the lockdown was the number of small businesses that went out of business (and are continuing to do so). Most small businesses survive month-to-month, paying next month’s rent, with this month’s takings etc., so to be shut down even for a month can be catastrophic – having talked to many small business owners in the city I have yet to have heard of one landlord offering any rent assistance, and the majority of the government/state assistance went to larger enterprises that employed more people etc. It is not the point of this article to argue the rights and wrongs of this situation, but to explain why the overall number of open small businesses (in Massachusetts) has decreased by 37% this year, with certain sectors being hit harder than others e.g., restaurants and similar establishments have decreased by 54.6%. Businesses paying high city rents have been disproportionately affected. The significance of this has not yet fully hit many people. If you are somebody who has adjusted your lifestyle so that you no longer go out to bars and restaurants or shopping on the “high street” etc., hearing about various establishments closing has yet to affect your current lifestyle, and the scale of such closures is not something you’ve directly experienced (and I include myself in this). When things get back to whatever “normal” looks like, the city landscape is going to look significantly different to what it once did.

Bars, shops, and restaurants etc. play a very important role in social control and crime prevention, with individuals and establishments acting as “place managers” which exert guardianship over certain locations and environments. In Routine Activities Theory, which states that for a crime/offense to be committed, there must be a motivated offender, a suitable victim, and the absence of a capable guardian; businesses can – and do – act as those capable guardians preventing crime(s) from being committed. An owner of a bar/restaurant has a financial interest in making sure that their customers have a pleasant experience and are not the victims of crime. To this end, they will make sure that at night their premises are well-lit, and they will often inform, liaise, and coordinate with local law-enforcement telling them when there is trouble, or they are suspicious of something going on in and/or around their premises etc. I am not trying to create the picture of an idyllic community, where everybody gets on, but to explain an informal role that small businesses often perform in the environments where they are located. A number of businesses located closely together may also attract a significant number of people at particular times of day/night that deter predatory criminals. However, when those businesses close, and get thinned out on a street, their role of guardianship decreases significantly, and a lone business with a reduced foot traffic, may start to attract offenders, instead. There is a security synergy that businesses create when there are a certain number of them in an area, and when the number is reduced at a certain point, this gets lost. The major high streets, with large stores, in extremely well trafficked areas, are unlikely to experience this, but certain other parts of the city in all likelihood will.

A closed business usually means an empty building, and empty buildings have an effect upon an area’s crime rate – not just because empty properties attract certain types of crime, such as prostitution and drug dealing. A swath of empty buildings can be a signal of a neighborhood’s deterioration and be a signal to criminals, especially drug dealers, that this is a good area to move in to, as there is a lack of social control in the area. An empty building allows a drug dealer and/or gang member a location to stand around without the risk of a business or homeowner raising a complaint. It may also be that as a neighborhood starts to depopulate, there are fewer reasons for law-enforcement to patrol it as regularly – it’s not that these areas become no-go areas for the police, but that there are other more populated areas to divert policing resources to. Neighborhood instability can also be increased if empty commercial/residential buildings in an area, result in the rentable value of other buildings in the vicinity dropping as well. If this situation maintains, it can change the nature of a neighborhood significantly, bringing in more transient businesses and individuals; and as the neighborhood changes, force historically long-serving and stable residents to move out. Such things are more likely to happen if a neighborhood borders one which has already experienced such a transition etc.

None of these things are inevitable, and there is nothing to suggest that certain Boston neighborhoods have been impacted in a way that would create the conditions for these things to occur, however there has been enough research and empirical findings to suggest that when the “right” mix of property usage changes, and buildings start to lie empty, crime has a habit of finding its way in.